|

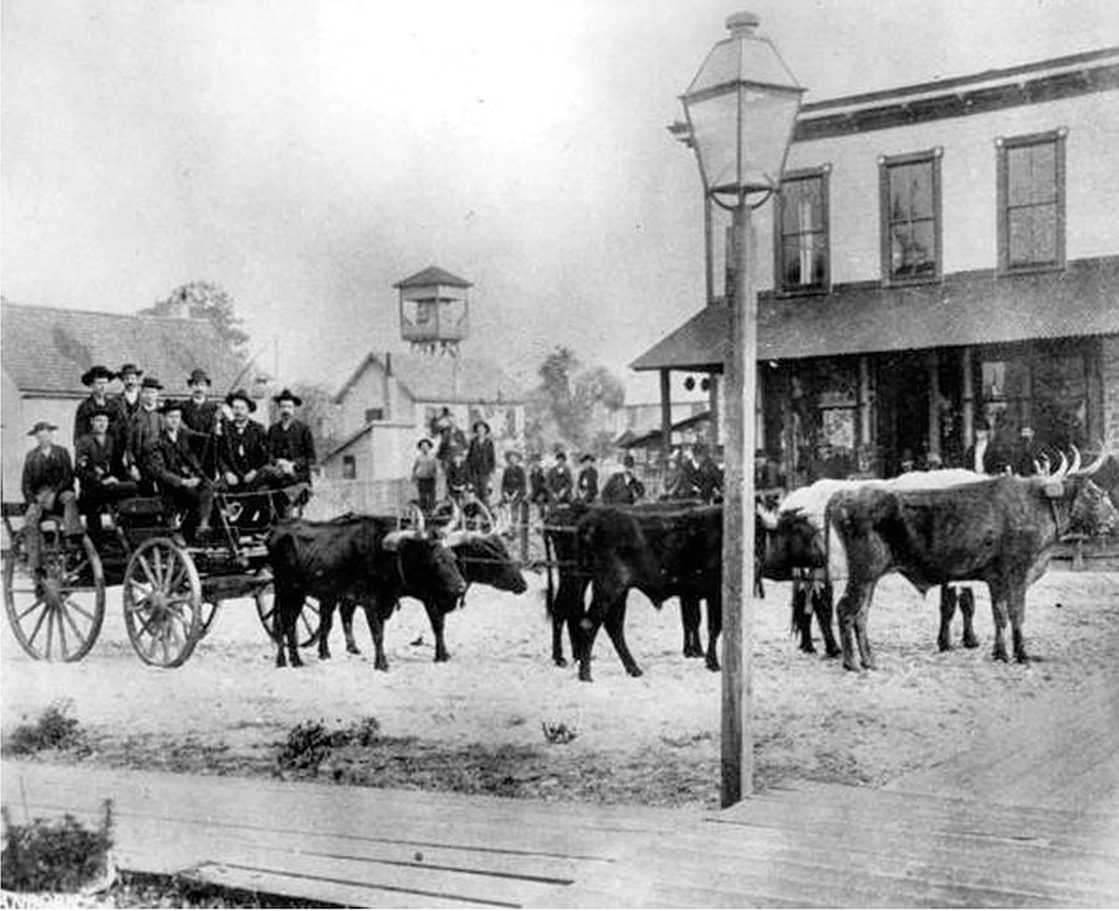

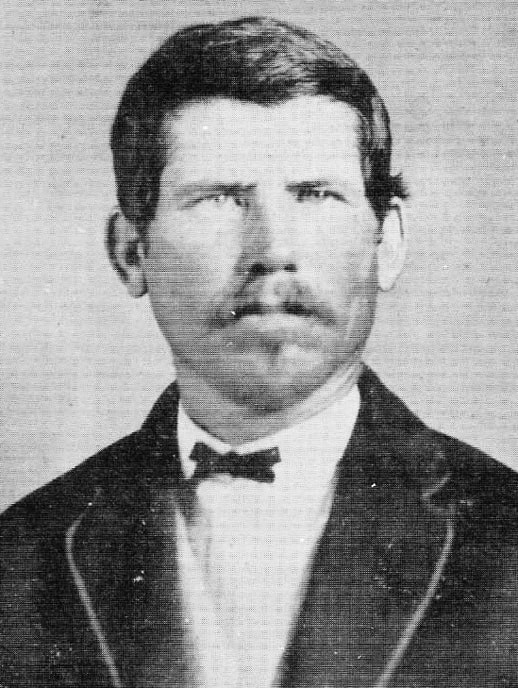

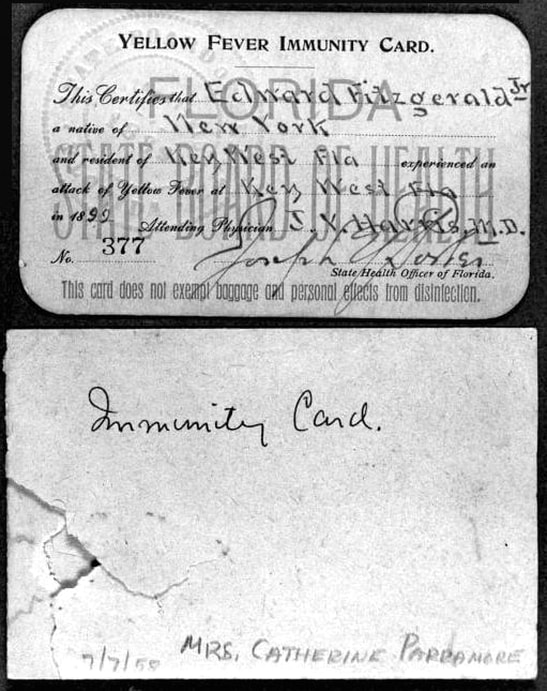

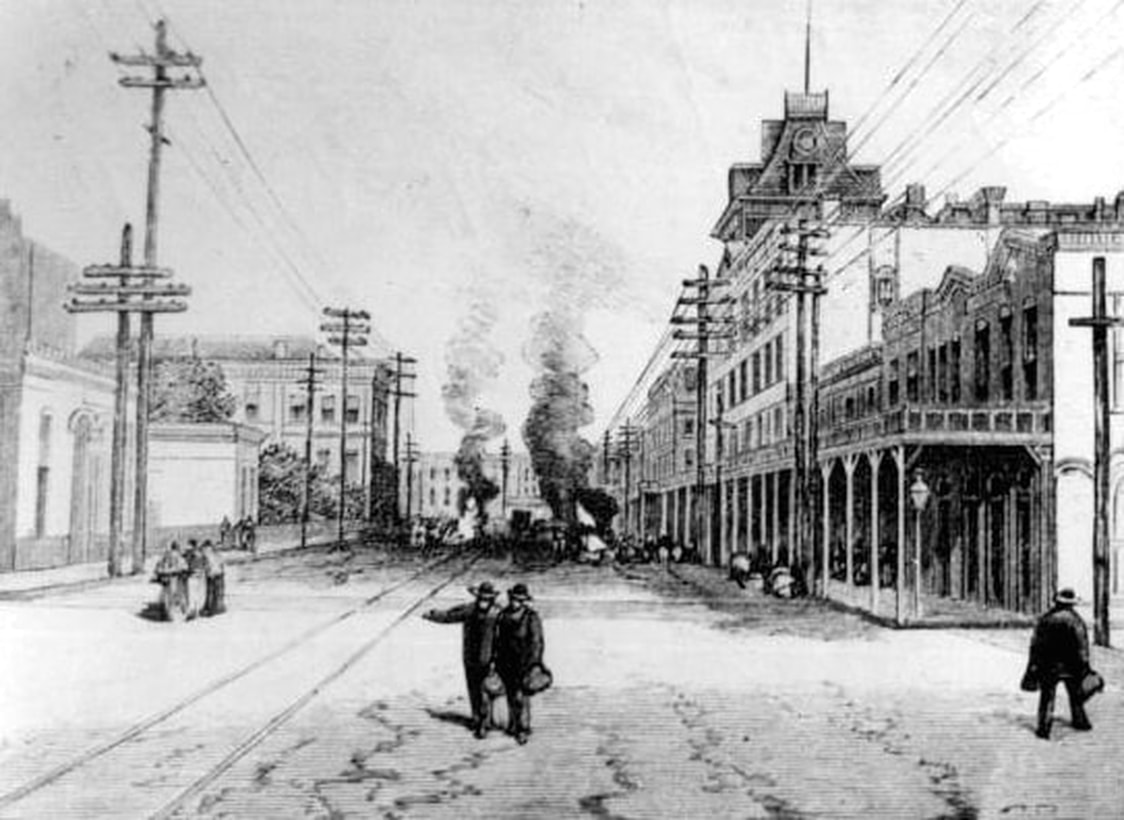

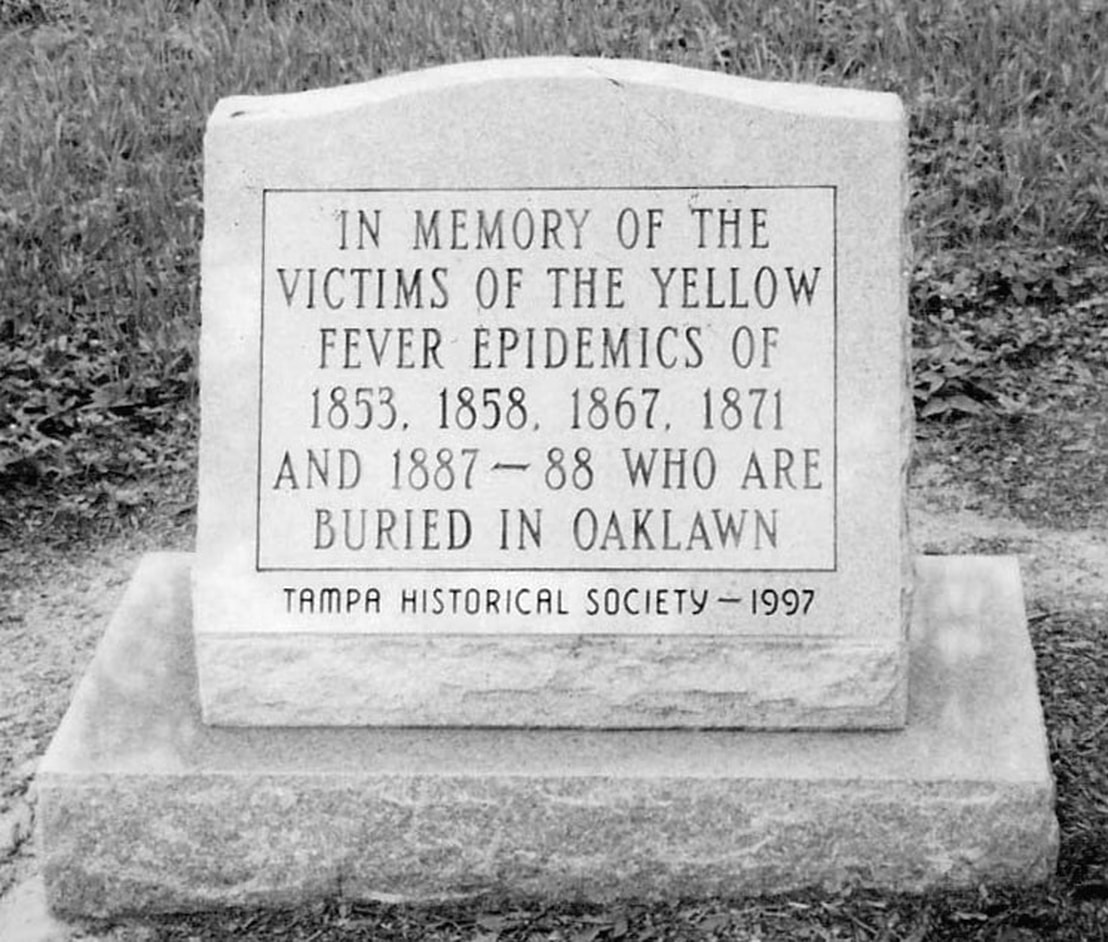

In 1887-1888, Tampa experienced the worst of the Yellow Fever epidemic! Death is not always gentle or timely. As you visit Oaklawn Cemetery, Tampa's c.1850 public burying ground at Morgan and Harrison Streets, it is a jarring fact that many of the early Tampans interred in that peaceful spot died in violent and painful conditions, and many at a young age. Most of Tampa's founding families lost members in that fashion. They were victims of yellow fever, a grim epidemic that struck Tampa repeatedly in the city's early history–five times, from the city's charter in 1850 to 1905, when the last case was reported. To a doctor or nurse at the time of the final incidence, the causative agent of yellow fever was well-known. However, in Tampa's pioneer decades–the 1820s to the late 1890s–the disease was still a frightening mystery, a cruel and unwelcome visitor that came and went without warning. It was called bronze John, bilious fever, the saffron scourge, and yellow jack–all these names derived from the jaundice that usually accompanied the disease. The last name, yellow jack, referred to the yellow flag - called a jack in nautical parlance - that ships had to fly when under quarantine for an outbreak on board. Yellow fever was a pestilence brought to the New World as part of the sad inheritance of slavery since it traveled in slave ships from West Africa, where it was and remains endemic, to the New World. It first appeared in Cuba and North America in the late 1600s and, by 1800, was a regular feature of the epidemiological landscape in the Antilles. The Southern U.S., especially port towns with their frequent exposure to strangers and strange diseases, quickly became a target for the disease. It struck with depressing frequency in Charleston, Savannah, New Orleans, Jacksonville, Pensacola, St. Augustine, and Key West. It first came to Tampa in 1839, assailing the Army post at Ft. Brooke Yellow fever, caused by one of a group of disease agents called flaviviruses, is a form of tropical hemorrhagic fever. It is a distant cousin of Ebola, though its symptoms are not quite as contagious or horrifying. Yellow fever is frequently fatal. Its victims die in great agony, usually racked by convulsions and delirium, bleeding profusely from the mouth and nose, and vomiting a substance (nux vomica) like black sand. The disease was particularly frightening in the nineteenth century because of its unpredictable contagion and course. Small children, the elderly, and women often survived or escaped contracting the disease, while strong adult males fell violently ill. Yellow fever's onset was rapid and without warning. Victims were frequently overcome while walking in the street or engaged in lively conversation; terrible exhaustion suddenly seized them, and they were desperately sick within hours. The yellow fever seemed sometimes to have a cruel sense of humor. After days, symptoms often remitted, and victims might appear to recover, to sit up, take food, and have diminished temperatures. Just as often, they would relapse after a few good days or hours into the horrifying, terminal phase of the disease. Unless a victim successfully developed antibodies to the disease, death was inevitable. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, there was no known cure nor accurate understanding of yellow fever's transmission mode. Sadly, there was also very little that could be done to ease the suffering of victims. Some of the treatments in vogue contributed to the casualties rather than minimizing them. Patients were given strong purgatives or bled aggressively, weakening them considerably. Most doctors of the period failed to understand the disease, but that did not mean they were not observing it and trying to learn its ways. One medical man who studied yellow jack was local doctor John Perry Wall, born in 1836 near Jasper, Florida, and resident in Tampa since 1869. Wall graduated from the Medical College of South Carolina and served with distinction during the War Between the States, first as a surgeon at the Chimborazo Hospital in Richmond and later as a combatant among the Eighth and Fifth Florida Battalions troops. After the War, Dr. Wall moved with his young wife Pressie and their children back to the family home in Brooksville and then, in 1871, to Tampa, a rough town of around 1500 inhabitants. Wall was familiar with all the diseases that beset pioneer Tampa–cholera, typhus, malaria, scarlet fever, dengue fever, dysentery, tuberculosis - but his path and yellow fever crossed for the first time singularly and tragically. The same year he moved to Tampa, the doctor went aboard a steamer in Tampa Bay to treat a desperately ill cabin boy. The boy recovered, but Wall took away the disease–yellow fever–which he then passed on to his wife Pressie and their fourteen-month-old daughter. Wall recovered, but his wife and daughter died within a few days. The event focused John Wall's mind on the disease, and he read all he could find on its probable causes. Epidemiology and the study of infectious diseases were then in their infancy as medical disciplines. There needed to be more reliable information in the 1870s on yellow fever. The disease was thought by some to be a variant of malaria. Others believed it to be a more potent form of dengue fever, which is indeed related, though a much more severe illness. The prevalent opinion was that it was caused by miasma, or "bad air," the gases given off by swamps, rotting vegetation, or accumulated human and animal waste in a tropical climate. The germ theory was brand new, though Wall, a staunch proponent of the disinfecting regimes of Lister, believed in what was then called "fomites," contaminated bedding, clothing, and even housing that could spread disease by contact or proximity. In good clinical fashion, Wall began to study the incidence patterns surrounding yellow fever. He noted that the disease was prevalent in the summer and disappeared with cold weather. The disease attacked white healthy males more frequently than African Americans or Cubans, who were thought (correctly) to have some degree of immunity. People who did not go outside after dark rarely got the disease. This protected group included most children, typically kept indoors at night. It is unknown whether Wall read the work of Dr. Louis-Daniel Beauperthuy, a South American doctor who had suggested as early as 1854 that the mosquito's bite spread yellow fever. Still, by the mid-1870s, Wall began to suggest that mosquitoes were involved in the disease cycle and that people should protect themselves from their bites. The reaction of the popular–not to mention the medical–press was rapid, intense, persistent, and ridiculing. For nearly fifteen years, Wall endured jibes and anger from many quarters, civic and medical, for his suggestion that sanitation alone would not eradicate the disease that was quickly proving to be the biggest obstacle to Florida's development. While Wall sometimes equivocated on the best ways to handle outbreaks, he made it clear that prevailing methods of prevention and correction were ineffective. These methods included burning barrels of tar at crossroads and in public streets, so-called "shotgun quarantine" (sequestering infected and suspect persons in tent hospitals from which they were prevented from escaping by armed guards) and spreading lime and chlorate of mercury in infected areas. The fever dead were buried in metal coffins or mass graves under a blanket of quicklime. The only effective measure against the disease was also the least popular: depopulation. When a community was attacked, its residents fled, preferably inland, as far and as fast as they could. They abandoned their goods, and property was sometimes looted or destroyed. A fever town's economic and governmental structure readily collapsed, and lawlessness reigned. This was the case in 1887-1888 when Tampa experienced the worst yellow fever epidemics. For quite a long time, the local press refused to acknowledge that the disease afflicting more than one-third of Tampa's 3000 inhabitants was yellow fever, preferring to designate it as the milder dengue fever or, more usually, to ignore it completely. After all, big projects were in the works in Tampa. V.M. Ybor and Ignacio Haya had opened large cigar factories just east of Tampa; jobs, money, and immigrant workers were streaming into the community. The railroad had arrived two years earlier with Henry Bradley Plant, and Plant was now proposing to build one of the world's largest and most luxurious hotels on the banks of the Hillsborough River. In December of 1888, The Tampa Journal reported that "Tampa is healthy and prosperous," even though there had been over 1000 cases of yellow fever and more than a hundred had died. Some critics - most of them analyzing the epidemic after the fact–criticized Dr. Wall for not being more aggressive in identifying the public health threat at the time or moving in concrete ways to address it. They pointed to Wall's position on the Board of Trade and his many growth-promoting activities in Tampa as reasons he might have dampened attention to the disease. Taken as a whole, the facts of John Wall's extraordinary intellect, training, experience, and medical conscience refute his critics. No amount of "booster-ism" would have caused him to endanger public health consciously. Nor did he, as some have suggested, overlook the cause of the disease and its prevention. Even putting aside the nearly impossible task of confronting, on every side, the naysayers in the press and the whitewashing efforts of local businessmen, Wall was still hampered by what we now know to have been contemporary and widespread scientific conservatism. In an age where many medical men still believed in humors and vapors, Wall was reluctant to credit that which he could not see or prove existed with the cause of disease. For this otherwise imaginative man to believe that an invisible microbe could be passed from an infected human's blood to a new victim by mosquito bite would have required a suspension of disbelief akin to seeing fairies. Nevertheless, by the early 1880s, Wall was convinced that–despite widespread belief to the contrary–filth and "miasma" did not cause yellow fever but rather an invisible agent or microbe connected somehow to mosquitoes in an infected area. How deep was Wall's unexpressed conviction that the so-called "treetop mosquitoes" spread yellow fever? This is still a matter of conjecture. He remained publicly undecided on the subject until his death. Still, he was equivocal on many things, including the effectiveness of a State Board of Health (for which he fiercely lobbied, despite his doubts and criticism), the Florida Medical Association's work, and the general insight of doctors. On his death in 1895, Wall addressed the Florida Medical Association at a meeting in Gainesville. Still campaigning against the stubborn adherence of the American medical establishment to the theory that "miasma" caused yellow fever, Wall suggested heatedly that rather than abandon their long-disproved theories, doctors would "exalt humbug at the expense of science and truth." Wall barely finished his speech before he collapsed at the podium and died of apparent heart failure. The penetrating insights of the Tampa doctor's lecture were lost in the general hubbub following his sudden demise. Regarding the cause of yellow fever, it waited for a team of American researchers in Cuba and the U.S., under the leadership of Dr. Walter Reed and including the Cuban physician Carlos Findlay, to definitively expose the Aedes aegypti mosquito as the vector of the disease. That took place in 1901, too late to clear a cloud of public opinion from John Perry Wall's reputation and far too late to vindicate the Tampa doctor himself, who had been dead by then for six years. Tampa, released from the recurrent scourge of yellow fever, has forgotten the disease, the debate, and the doctors who figured in this cruel chapter of pioneer history. After 112 years of freedom from "yellow jack," Tampans say it too seldom and softly: "Dr. Wall, you were right." CIGAR CITY MAGAZINE- JULY/AUGUST 2007 Art & Photography Contributors: Hillsborough County Public Library, Tampa Bay History Center, The Florida State Archives, The Tampa Tribune/Tampa Bay Times, University of South Florida Department of Special Collections, Ybor City Museum Society, private collections and/or writer. Maureen J. Patrick A Tampa native, Maureen J. Patrick was the President of the Tampa Historical Society from 2006-2009 and Editor of The Sunland Tribune (a journal of local history.) Patrick holds an advanced degree in cultural history. FOLLOW CIGAR CITY MAGAZINE

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2013

Categories

All

|

Cigar City is a Florida trademark and cannot be used without the written permission of its owner. Please contact [email protected]

© 2021 Cigar City Magazine. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

© 2021 Cigar City Magazine. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed