|

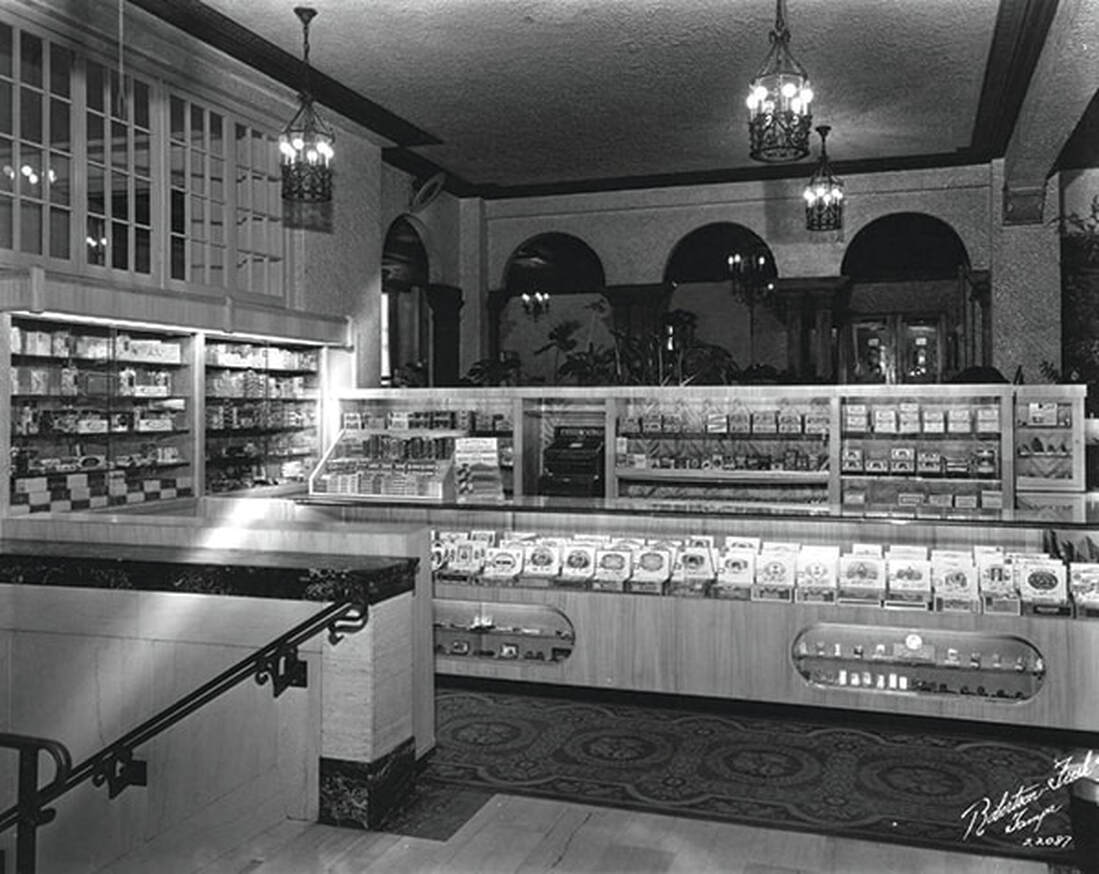

The red neon "Open" sign in the Franklin Street News Stand window would flicker on at 7 A.M., followed by the neon signs for the news stand's neighbors–the Shoe Hospital and Carmen's Sandwich Shop–shortly after that. A block away, the homeless people sleeping in front of Sacred Heart Church would wake up, roll up their blankets and seek shade from the hot sun. And then, for the next two hours, downtown would lay quiet, waiting for the rush of attorneys, judges, politicians, and financial analysts who made downtown their home from 9 to 5, Monday through Friday. Packed into their offices, they left for only an hour each day to eat at one of the few restaurants scattered throughout downtown and then disappeared when work ended. The neon signs would shut off. The homeless would return to Sacred Heart's lawn, and the downtown would become a ghost town again. Until a few years ago, this was the average weekday scene in downtown Tampa. Today, though, this once-forgotten area of the city is bustling with life 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Condominium towers adorning just about every corner of downtown Tampa are filling up with residents. To accommodate these downtown residents, new restaurants, bars, and cafés are popping up around the towers. A new Tampa Museum of Art will open this fall. Electric golf cart taxis shuttle people about. Business at the Tampa Theatre has never been better. Even venerable dive bar The Hub opened new digs in 2002. Yes, downtown Tampa is alive again. There are reasons to live and play in downtown. Vehicular and pedestrian traffic fills the streets and sidewalks from the early hours of the morning until, well, the early hours of the morning. But there is one piece of the downtown puzzle that is incomplete, still, one section of downtown that resembles the ghost town of a few years ago–Florida Avenue from the south side of Zach Street to I-275. All new businesses have yet to open up on this seven-block stretch. No condominium towers are being built. Even the presence of the Federal Courthouse has yet to be able to resurrect this section of downtown. Since the renaissance of downtown began, this area of Florida Avenue has desperately sought a cornerstone business. For years no one stepped up. Hope has finally arrived, though. The Floridan Palace is coming. This 19-story, 164,000-square-foot hotel in the 82-year-old Floridan Hotel building at 905 N. Florida Ave. will house 213 hotel rooms, a bar, a restaurant, retail space, a ballroom, and a convention center. "This is going to be Tampa's Waldorf Astoria," said hotel spokesperson Lisa Shasteen. Clearwater hotel developer Antonios Markopoulos purchased the building in 2005 for approximately $6 million and has since personally poured millions more into making it a nearly exact recreation of the historic 1920s-era Floridan Hotel. Its original bar and marble staircases have been restored, as have its artistic tiled ceilings displaying green wreathes, purple lilies, and yellow pears. An old mailbox featuring mail slots for every room in the hotel was found, cleaned, and will be used again. Even the original Floridan Hotel sign has been refurbished and again adorns the exterior of the building. "We're saving as much of the original hotel as we can," said, Shasteen. That which could not be restored has been recreated. Replicas of the original golden chandeliers have been installed. The wooden window arches were rotted, so new ones were constructed. Handmade iron railings resemble those that once protected the stairway, as have the wooden balconies that once overlooked the first floor. "It will look as close to the original hotel as possible," said Shasteen. "And it hasn't been easy." When Markopoulos purchased the building, it had been abandoned for 30 years. Crows and vultures shared the hotel with squatters, who took over the suites and turned the building into their dormitory. A suite on the 17th floor was turned into a bar for the tenants. Another room stored several bicycles. Numerous rooms were wallpapered with comic strips. "When he bought the hotel, people told him it was an impossible project. But one thing I learned is never to tell him it's impossible. He doesn't like to hear the word no," said Shasteen of Markopoulos, who sold the five hotels he owned in Clearwater, got bored, and decided he needed a new challenge. "And this building is a challenge." Despite working on restoring the hotel for four years, a completion date has yet to be set. The floors have been stabilized, the first coat of plaster has been laid on the walls, and the historic features have been restored, but the building is still a shell for the most part. There is much work to be done. When the hotel is complete, Shasteen believes it will be the cornerstone business the area needs. She thinks the attorneys, judges, and jurists at the nearby federal courthouse will dine at the hotel's restaurant. She believes weddings at Sacred Heart Church will use its 10,000-square-foot ballroom. She thinks business people will use its 11,000-square-foot convention center. She believes downtown residents will flock to its posh bar. And she believes men and women worldwide will stay in its first-class accommodations. "A lot of people who perform at the Performing Arts Center want to stay somewhere special, somewhere unique to Tampa," said Shasteen. "This will be the place." The restoration is already having a positive effect on the neighborhood. Shasteen was recently inside the old Kress building, located across the street from the hotel, with its owner Jeanette Jason. Shasteen said the Kress building is in better shape than the Floridan was, and Jason is discussing renovating it for either office or retail space. "When that happens, I think these other businesses will open up, and this part of downtown will be full of life again," said Shasteen. "The area around the hotel used to be very busy," remembered Gus Arencibia, who bartended at the Floridan Hotel's Sapphire Bar for 20 years. "I used to meet my wife near the hotel, and we'd walk to Maas Brothers and Kress and Tampa Theatre and all the other stores. We couldn't walk one block without stopping to talk to at least ten people we knew." And the epicenter of the downtown activity was the Floridan Hotel. By day, businessmen and gangsters visited the Sapphire Room for a sandwich and one drink. "They never got drunk," said Arencibia. "One drink only. And there was never a rare moment." The Sapphire Bar's daytime clientele was famous for making crazy bets among one another. Two men once made a $100 bet they could drive from the hotel to the Seabreeze Restaurant in Palma Ceia without stopping their car once, rolling through all stop signs and red lights. "And they did it," laughed Arencibia And then there was the time gangster Jimmy Lumia bet someone $50 that he could buy a ticket at the Tampa Theatre without getting out of his car. "He drove up the sidewalk to the ticket office and motioned for the ticket girl to bring him a ticket," remembered Arencibia. "And then he drove back to the hotel and won the bet." By night, GIs danced alongside Tampa's elite and the hotel's celebrity guests, including Jimmy Stewart, Jack Dempsey, Elvis Presley, and Charlton Heston over the years. The Floridan Hotel was also where Gary Cooper wooed actress Lupe Velez in 1930 while they stayed there while filming "Hell Harbor." A dress code was firmly enforced–women had to wear a dress, and men had to wear a jacket and tie. Local musical legends like the late Columbia Restaurant owner and violinist Cesar Gonzmart performed. The house rule forbade women from sitting at the bar without a male escort. "There were so many women dancing that the Sapphire Room was renamed the Sure-fire Room by some of the local GIs," explained Arencibia. "My family lived in a three-bedroom suite with a living room and kitchen and multiple bathrooms, so these weren't small suites we lived in," explained 84-year-old Mary Jim Scott, who lived in the Floridan Hotel from age 2 - 24. Her father was the hotel manager, and their suite was on the 19th floor. "This was before apartments and condominiums were common. So we had a lot of people who rented suites full-time." The hotel was a playground for Scott. Her father built her a playhouse and fishpond on the hotel roof, where she would spend much of her time. She'd climb on the walls and even swing by the hotel's sign, 20 stories up. "At the time, the hotel was the tallest building in Florida. I don't know how I didn't fall off," she said. "Looking back, I'm lucky I didn't die." One day, when she was 7 or 8, she threw all her toys off the roof. When the desk clerk saw toys shattering all over the sidewalk, he immediately called Scott's father, who turned ghost white and rushed to the roof to stop his daughter. Scott was entertaining the permanent guests when not causing mischief on the roof. With the help of her father's secretary, she published her own newspaper full of harmless gossip about the guests. "Oh, the stories were about where guests were going or where they were eating," she said with a smile. "It was so simple, but the permanent guests seemed to like it." She also performed plays in the mezzanine for everyone in the hotel. She would write the play, the engineers and maids would rig a curtain, and Scott, her friend, and fellow resident Jackie, would star. "We made all the employees and permanent guests come," laughed Scott. "And there were a lot of employees–over 400. The hotel was like a small city. We had our own engineers, housekeepers, bell captains, bell boys, desk clerks, telephone operators, and so on. We even had our own detective because, with that many residents and guests, we were sure to have problems. Nothing ever serious, though. Just small problems." When the 1960s rolled in, the hotel began experiencing significant problems. Suburban malls and shopping centers became the chic places to shop, sapping downtown Tampa of its patrons and the hotel of its regular diners and drinkers. Chain hotels took the Floridan's guests. In 1966 the Floridan closed as a commercial hotel and remained open for long-term renters only. By the early 1970s, suburban apartments became more common, providing renters with more options, and the Floridan soon served low-income tenants only. After several small fires in the 1980s, the hotel was closed and sat empty for the next three decades. Then, Markopoulos purchased the building in 2005. "And I couldn't be happier," said Scott. "I can't wait for it to open." Nor can the rest of downtown Tampa, as the Floridan Palace will be the final piece to the revitalization puzzle. Downtown Tampa is alive again, and its crown jewel will soon be as well. CIGAR CITY MAGAZINE- MARCH/APRIL 2009 Art & Photography Contributors: Hillsborough County Public Library, Tampa Bay History Center, The Florida State Archives, The Tampa Tribune/Tampa Bay Times, University of South Florida Department of Special Collections, Ybor City Museum Society, private collections and/or writer. PAUL GUZZOPaul Guzzo is a reporter for the Tampa Bay Times. He found the lost segregation-era all-black Zion Cemetery. His unique beat also includes the local film industry, Tampa history, professional wrestling, and the odd and unique people who make up this area. Guzzo has been a journalist in Tampa since 1999, including a senior writer for Cigar City Magazine and Tampa Mafia Magazine. In his younger years, he was an independent filmmaker best known for an award-winning documentary on Charlie Wall, Tampa’s first crime lord. FOLLOW CIGAR CITY MAGAZINE

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2013

Categories

All

|

Cigar City is a Florida trademark and cannot be used without the written permission of its owner. Please contact [email protected]

© 2021 Cigar City Magazine. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

© 2021 Cigar City Magazine. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed