|

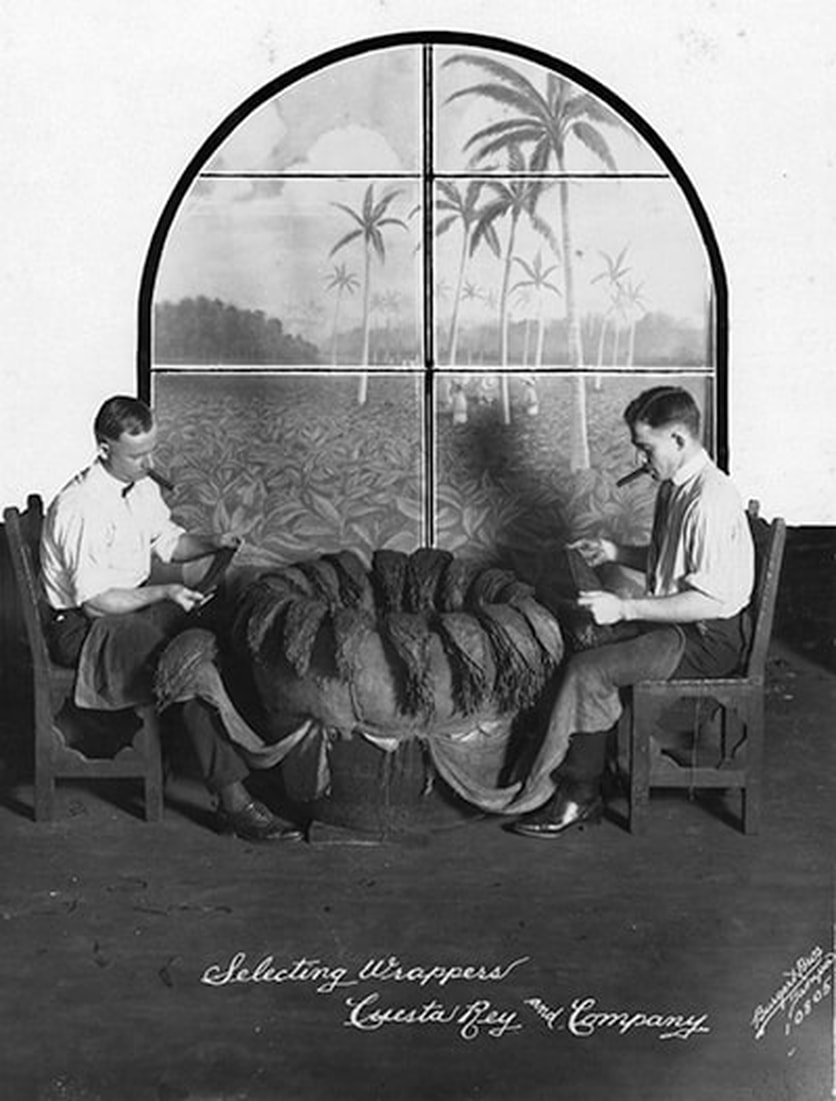

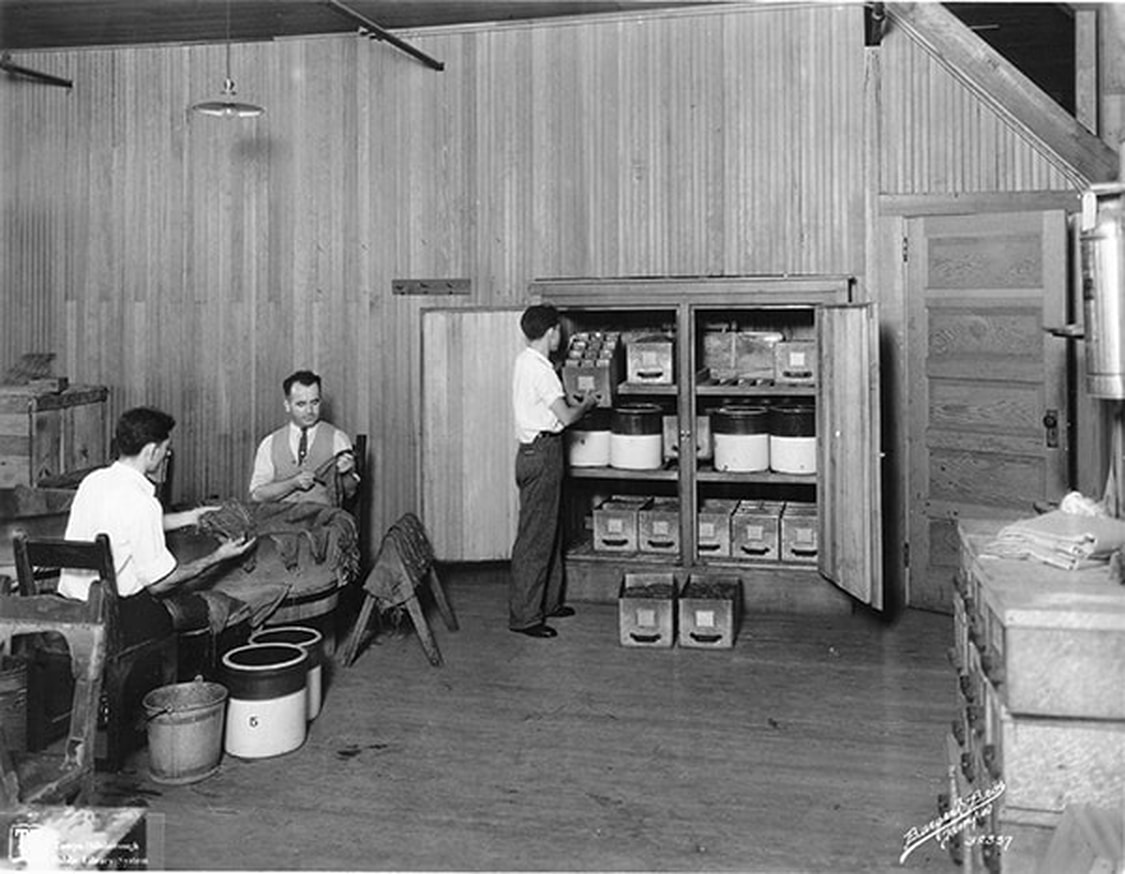

Far better it is to dare mighty things, to win glorious triumphs even though checkered by failure than to rank with those poor spirits who neither enjoy nor suffer much because they live in the gray twilight that knows neither victory nor defeat. -Theodore Roosevelt (1858 -1919) In our factory, the regidores (selectors) sit on opposite sides of a broad barrel sorting tobacco leaves in the good intense light in the large north-facing windows. Two men sit at each barrel. The regidores pay close attention to the leaves used as wrappers as they sort according to size, the look of the veins, and dry or oily texture. Sometimes there can be up to nearly 100 grades of wrappers for the various types of cigars made. These wrappers are the leaf that adds the finished wrap to the cigar filler. Stacks of leaves are placed along the edge of the barrel, and when the number in the stack reaches about 25, it is bundled up and ready for the tabaquero, the cigar maker, to use according to the size and quality of the cigar he is making. In some factories, at the end of the day, the regidores collect the cigars made with the leaves they selected to see the finished product in a properly rolled cigar. Men apprenticed for several years before becoming regidores. Selecting the wrappers for the cigar workers requires learned skills, good light, and a keen eye. Many habaneros only want the wrappers chosen by specific selectors. I tell you this so that you will understand the esteem of these workers and the beginnings of the current situation in our cigar factories that started in June of this year, 1910. The manufacturers sent away the selectors and brought in others of their choosing to the dismay of the selectors and the cigar workers. Many of the selectors and cigar makers of the large factories belong to the Cigar Makers International Union. There were many grievances. The selectors were told they needed to be training more recent apprentices. The selectors felt they needed to be taught more. The workers continued to be dissatisfied because the manufacturers were not adhering to the recently agreed-upon wage and price scale. Now they were hiring workers who did not belong to unions and laying off workers as soon as they joined a union. The manufacturers wanted the workers to strike to bring in open shops without unions being present. If that happened, the workers would have no one fighting for their rights. After the defeat of La Resistencia, a local union, in the 1901 strike, the workers were bitter, and their union was gone. The strike lasted four months, and cigar workers' families were hungry. Another union, the Cigar Makers International, stepped in and started recruiting new members. There were other unions, but the CMIU had grown to 6,000 members by now. In July of this same year, workers left the Celestino Vega and Company factory in West Tampa when the owner refused to recognize the CMIU. This was the final straw for the workers. Five factories had closed by the end of July, and the strike was underway. By the end of August, 12,000 men were out of work. The factories sit quietly. El lector does not sit on the tribunal and read to workers, no cigars are made, and workers sit idle. My friends are frustrated and angry. They want to work and need to work but are afraid they will lose their union representation if they concede to the manufacturers. Many have left Tampa for other Florida cities and northern states or returned to Cuba to seek employment in the cigar factories there. Others work in farming or other businesses to feed their families. My job as El Lector is also silenced. I spend idle time translating books and documents and teaching English to students. Many hours I have spent in the labor temple and cafés drinking cups of strong Cuban coffee and listening to the discussions about the strike. I speak words of encouragement to the workers. It is a brutal fight, but theirs is a just cause. Our hopes were raised at the August 11th demonstration of support by not only the cigar workers but also by the unions and men of other trades. The Joint Advisory Board of the Cigar Makers International Union organized the evening parade. It moved through Tampa down Florida Avenue past the courthouse, down Franklin to Seventh Avenue, and into Ybor City. Hundreds of supporters belonging to the unions for carpenters and joiners, sheet metal workers, bricklayers, and longshoremen from the Port of Tampa joined along the way. Supporters came from St. Petersburg and other communities around Tampa. A large uniformed band played while accompanying the parade. Seeing the women and men shouting encouragement along the way and waving hats and handkerchiefs made us stand tall and proud. It was a warm August night, and the streets were illuminated only by the two torches we carried as the groups walked from the shallow pool of light from one street light to the next in the distance. Some men built a platform on the vacant lot at 19th and 7th Avenue. Speeches were given to a crowd of thousands at the parade's end. José de la Campa, the President of the Joint Advisory Board, began the introduction of the other speakers by explaining the difficulties the cigar makers had endured from the manufacturers. The speech was so beautiful that it made my heart swell with pride in our people. The band played inspiring music throughout all of the speeches, and, in the end, Mr. de la Campa bid the crowd good night with a wish for us to go in peace and show the people of Tampa we are law-abiding in our demonstrations. And we did go in peace. It was a quiet night in the streets of Ybor and West Tampa. The days following were not so quiet. The manufacturers offered some modest concessions but refused to recognize the union. That was unacceptable. Several factories announced they would reopen as an open shop, and those wanting employment could return. This resulted in street fights between the indignant union men and those enticing them to return. When they opened the Santaella and Company factory in West Tampa, fights broke out, and three were arrested, but no one went to work. It was calm at the Berriman Brothers in Ybor, but again no one went to work. Within a few days, the factories closed again. Now we have just passed Labor Day. As we hoped, the unions had big parades with floats, banners, and bands entertaining the community. As in the earlier parade, there was a lot of support from the other unions in and around Tampa. Later, speeches supporting the unions were given. Reverend Joe Sherouse of the Typographical Union told us of the various victories that strikes won for workers in other unions around the country this year. The workers cheered and were again inspired that success could also come to us. Again we wait. The enthusiasm fades more quickly each day. The men are tired of the harassment from the manufacturers and the union extremists. I think the unions want to fight more for having their union representation in the factory than for the welfare of the workers they represent. The cigar workers want fair treatment and good wages for the highly skilled work of making fine cigars. They want to feed their families with wages for hard work, not from some meager handout given in a miserly fashion from the unions. There were rumors the union would be out of money soon anyway. I do not have a good feeling about this strike. The manufacturers have their own "union" of sorts. The Clear Havana Cigar Manufacturer's Association makes decisions that all factory owners follow. As a group, they can be stronger than our unions. I hope this will soon be over. I miss walking through the factory smelling the warm tobacco and healthy sweat of working men. I miss reading to the workers while I listen to the chavetas slicing and trimming tobacco leaves and men laughing and shouting happy greetings to their friends. This may soon be finished, and we can return to the lives and livelihoods we love. Addendum This is a fictional account of how the strike of 1910 was felt by the workers from El Lector's view. The strike was not to be over quickly. It was long, hostile, and deadly before the end came in January 1911. Shortly after this account ended, on September 14, 1910, J.F. Easterling was shot as he tried to enter the Bustillo Brothers and Diaz factory, where he worked as a bookkeeper. As he lay in the hospital, the police arrested two Italian men from West Tampa who were suspected of the crime. While these men were not cigar workers, they were suspected of being hired by an extremist working inside the union. As they were transported from one jail to another, they were taken from the police by vigilantes and lynched from a tree on the corner of Grand Central Blvd. (Kennedy) and Howard. Later that month, Easterling died from his injuries and was laid to rest in Woodlawn Cemetery. Ybor and West Tampa simmered in unrest. The Balbin Brothers factory was burned, and fights erupted frequently. A Citizens' Committee was formed by local Tampa businessmen who said they represented the economic interests of Tampa. Others called the committee the "Cossacks of Tampa" for their patrols through the streets, breaking up union meetings, threats, illegal searches, and beatings. They violated the civil rights of anyone in their path. Even women and children were arrested for vagrancy if they were found begging. The laws of decency applied only to white "Americans." The cigar workers feared the Citizens' Committee and the union extremists. It was an ugly time in the history of Tampa. Samuel Gompers, President of the American Federation of Labor (CMIU's parent organization), was outraged at the tactics and complained to the Governor of Florida, who visited the city and met with the police and Mayor in Tampa. They decided that all actions by the police and citizens committee were justified. The union's Joint Advisory Board held an election at the end of September to see if the workers wanted to return to work or continue the strike. To ensure a fair ballot so that there would be "no intimidation or undue influences around the balloting place," the Board of Trade suggested representatives from the city and the Board of Trade be present to enforce a fair return and count of votes. According to the Tampa Morning Tribune, on October 11, 1910, it was "a farcical election." The results were 3,446 to 15 in favor of continuing the strike. "The vote itself is sufficient comment on whether or not the election was conducted as announced," the newspaper concluded. The strike continued. In October, the Joint Advisory Board became more defiant. The Tampa Morning Tribune ran an article outlining its proclamation, which stated the board would not be responsible for actions taken by workers "produced by the machinations of the enemy of the working class." Further, the board would ship the cigar workers out of the city if violence occurred. Other union workers rallied to the cigar workers' cause with similar proclamations of support. starving families to feed. The citizen patrols guarded factories and dispersed the picketing workers with threats, arrests, and beatings. The Citizens' Committee was made up of men who were hired guns, and their tactics broke not only the spirit of men and women but also the back of the strike. By January, the union's coffers were empty. Though some die-hards persisted, the union gave up and recommended that the workers return to work. The factory owners successfully stopped the unions for the second time in 10 years. Sources for historical information about the 1910 strike for both El Lector and the appendix: USF Special Collections that included City in Turmoil: Tampa and the Strike of 1910 by Joe Scaglione and Alterta Tabaqueros! Tampa's Striking Cigar Workers by George E. Pozzetta, Arsenio Sanchez collection Immigrant World of Ybor City by Gary Mormino and George E. Pozzetta Tampa Morning Tribune, June 1910-October 1910 Tampa Cigar Workers, by Robert P. Ingalls and Louis A Perez, Jr. CIGAR CITY MAGAZINE- JULY/AUGUST 2006 Art & Photography Contributors: Hillsborough County Public Library, Tampa Bay History Center, The Florida State Archives, The Tampa Tribune/Tampa Bay Times, University of South Florida Department of Special Collections, Ybor City Museum Society, private collections and/or writer. Gail ellisGail Ellis attended the University of South Florida, lived and worked in Tampa for 40 years. Devoting her time to writing now, she currently resides in New Port Richey, Florida. She told us the following, “Just so you know, you cannot get decent Cuban bread nor a cup of café con leche in Pasco County.” FOLLOW CIGAR CITY MAGAZINE

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2013

Categories

All

|

Cigar City is a Florida trademark and cannot be used without the written permission of its owner. Please contact [email protected]

© 2021 Cigar City Magazine. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

© 2021 Cigar City Magazine. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed