|

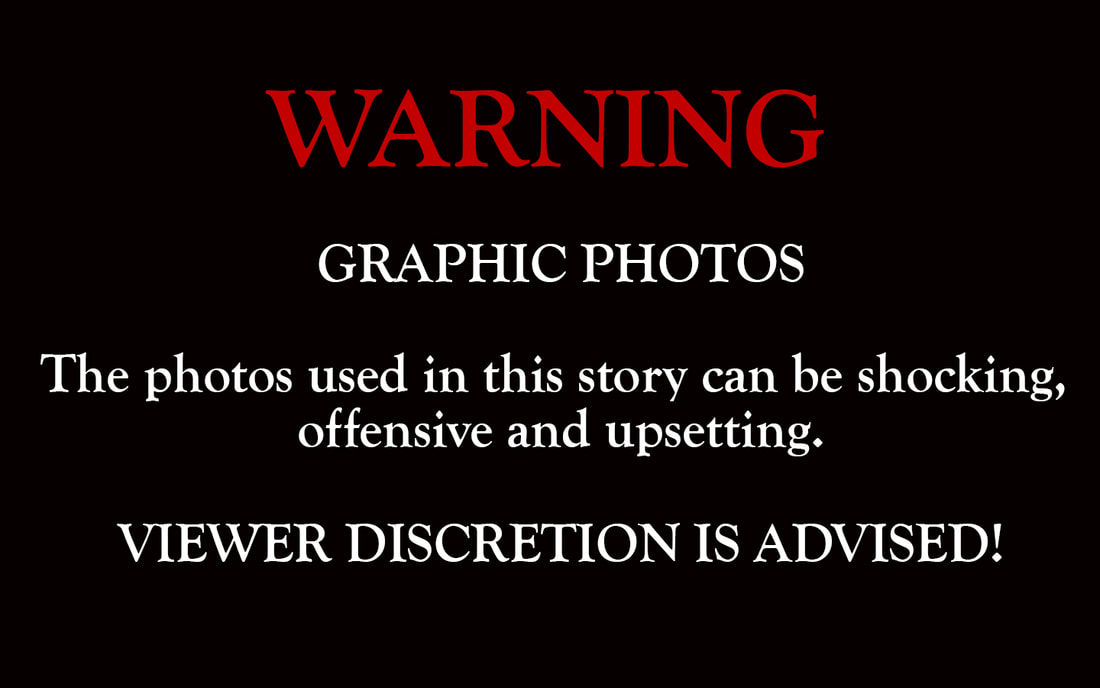

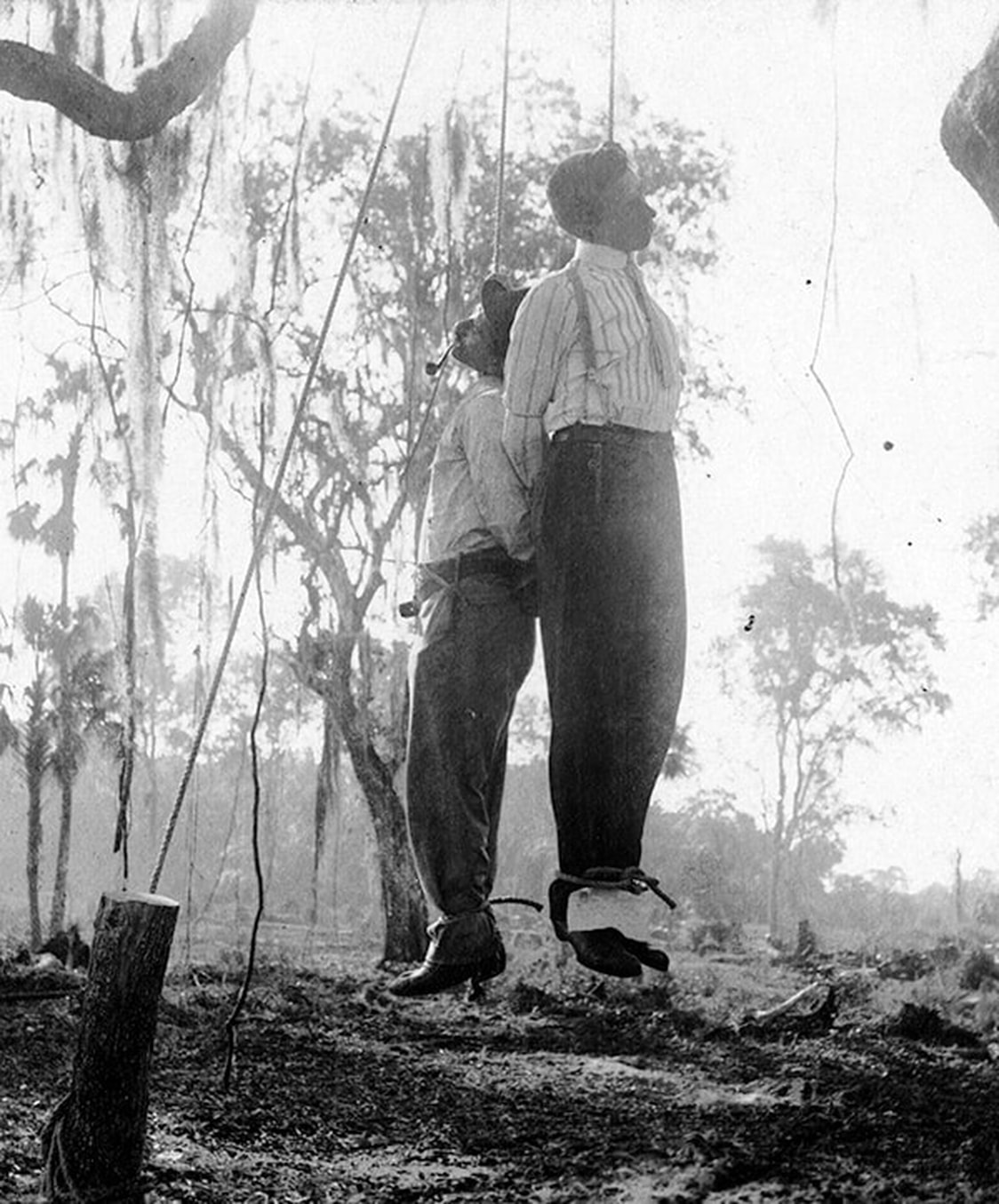

“Now is the time to make a decision.” Saying it, I surprise even myself. “The M. Fernandez Factory was called out yesterday, and the workers have joined the picket line. The Tampa Morning Tribune reports that Castange Ficcarrotta and Angelo Albano–two Italian anarchists–were found hanged this morning across the river in Tampa. I wait for this to sink in, and the workers, quietly setting up for a day of rolling or still shuffling into the galleria, all come to a stop. There is no collective sigh, no gasp, just their eyes watching me on the stand, and I can feel them staring; I can feel them beginning to shoulder the weight of what I have just told them. This strike has dragged on since June, the slow Florida summer doing little to alleviate the pent-up tensions. It’s all over the New York papers, too. The New York Times ran a story on Tampa’s “necktie party,” but I can’t bear to tell them that. “Retaliation,” I said. “They hung those two Italians because of Easterling, the American bookkeeper over at the Busillo Factory who was shot last week. Sheriff Kegan arrested them in West Tampa, charging both with attempted murder for the Easterling shooting. They were picked up yesterday afternoon on no proof and transferred from the West Tampa jail to the County jail last night. The Tobacco Journal reports that a mob of 60 men confronted the police escort on Howard Avenue. The Italians were placed in a hack and driven down Grand Central.” I can’t remember it ever being this quiet. Not a word. I scan their faces, perfectly still, as sunlight trickles in through the opened windows and a breeze begins to flow through the room. It would be gone by the afternoon as the air becomes still and the heat weighs everyone down. The workers here have held out through the summer, refusing to join in with the Cigarmakers’ International Union, refusing to join the line. They have families and kids. Most are too young even to remember the last time the Union won. 1889, I think. That was 11 years ago. They can’t afford to keep losing. I read more: “They found a message,” I said, my voice breaking slightly, but I don’t think they could tell. “A note tied to one of the bodies read “‘Beware! Others take notice or go the same way! We are watching you!’” Before I realized it, I had yelled it out to them. I didn’t mean to be so loud, but the words echoed around the rafters, bouncing back to me from the brick walls. I just stood there and let these threats, scribbled, and attached to a dead man’s shoe, settle on the workers. I stop reading and find myself leaning on the rail, trying to bring myself closer, stretching my arms out as if to grab them, snatch them up individually, and put them onto this platform with me. “They call this justice! They call this fair! This lynching, this attack on innocent men, is no accident! Everyone in this room knows there have been too many “accidents” like this!” I let the words echo and bounce into the rafters again and off the brick walls, and everything is quiet once more. The workers are still, their eyes fixed, their hands motionless as tobacco lies heaped on their tables unformed. I turn again to the papers, now strewn about, on the platform, and pick one up. “If that’s not enough,” I tell them, “They’re going to deport Jose De La Campa,” holding the front page of the Morning Tribune in the air. Now, everyone is looking around, and the whispers ripple like waves through the room. De La Campa, the young, charismatic union organizer, has been a celebrity since he arrived here from Oriente Province. The last time they arrested him, people applauded as the cops dragged him down the street in handcuffs while he just grinned. The Union Hall was always packed during his speeches, and the Tampa locals were always in the wings, watching, waiting for an excuse to arrest him, maybe bust him up a bit, send him to jail for a night so he’d have to cancel a speech or an important union meeting. Now, they had found an excuse to deport him back to Cuba, charging him with conspiracy and inciting a riot. “The Union has sent representatives to Havana requesting aid for all striking workers and will provide transport for those wishing to leave Tampa to secure work in Cuba. And the Union president is coming down from New York to meet with the manufacturer’s association. But if Tampa’s “citizens committees” are allowed to run loose in the streets, free from legal recourse, free to apprehend cigar workers and deport them–or worse– no one is safe.” I look out at the room of workers, all standing now, and my eyes meet with theirs; one by one, we connect. “Now is the time to decide. Will you continue to work? Will this factory continue to profit while De La Campa is deported? While Ficcarrotta and Albano hang motionless? Now is the time to decide.” The 1910 strike began in June and lasted through October, becoming one of Tampa’s bloodiest labor disputes. Throughout the five-month strike, the Cigar Maker’s International Union called dozens of factories out on strike. Several shootings, beatings, and deportations occurred as cigar workers, manufacturers, and Tampa’s business elite battled to control the lucrative cigar industry. Mr. Easterling, bookkeeper at West Tampa’s Busillo Brothers factory, was shot on September 14 and later died in the hospital. On September 21, in retaliation for the shooting, Castrange Ficcarrotta and Angelo Albano, two Italian labor organizers, were arrested in West Tampa and charged with murder. That evening, a mob hijacked a police escort transporting the two Italians to the County Jail. Mr. Ficcarrotta and Mr. Albano were found the next day, hung together from a tree along Grand Central Avenue, today’s Kennedy Boulevard. A note was tied to the shoe of one of the men, reading in part, “Beware! Others take note or go the same way!” Ficcarrotta and Albano’s involvement in the shooting of Easterling was never proven, and no one was ever charged with their hanging. Note: El Lector is fictional, but the story is based on an actual occurrence. CIGAR CITY MAGAZINE- JULY/AUGUST 2007 Art & Photography Contributors: Hillsborough County Public Library, Tampa Bay History Center, The Florida State Archives, The Tampa Tribune/Tampa Bay Times, University of South Florida Department of Special Collections, Ybor City Museum Society, private collections and/or writer. MANNY LETOManny Leto is the Executive Director for the Preserve the 'Burg in St. Petersburg, Florida. He also worked as Director of Community Outreach for the Ybor City Museum Society, then became the managing editor of Cigar City Magazine and Director of Marketing for 15 years with the Tampa Bay History Center. FOLLOW CIGAR CITY MAGAZINE

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2013

Categories

All

|

Cigar City is a Florida trademark and cannot be used without the written permission of its owner. Please contact [email protected]

© 2021 Cigar City Magazine. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

© 2021 Cigar City Magazine. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed