|

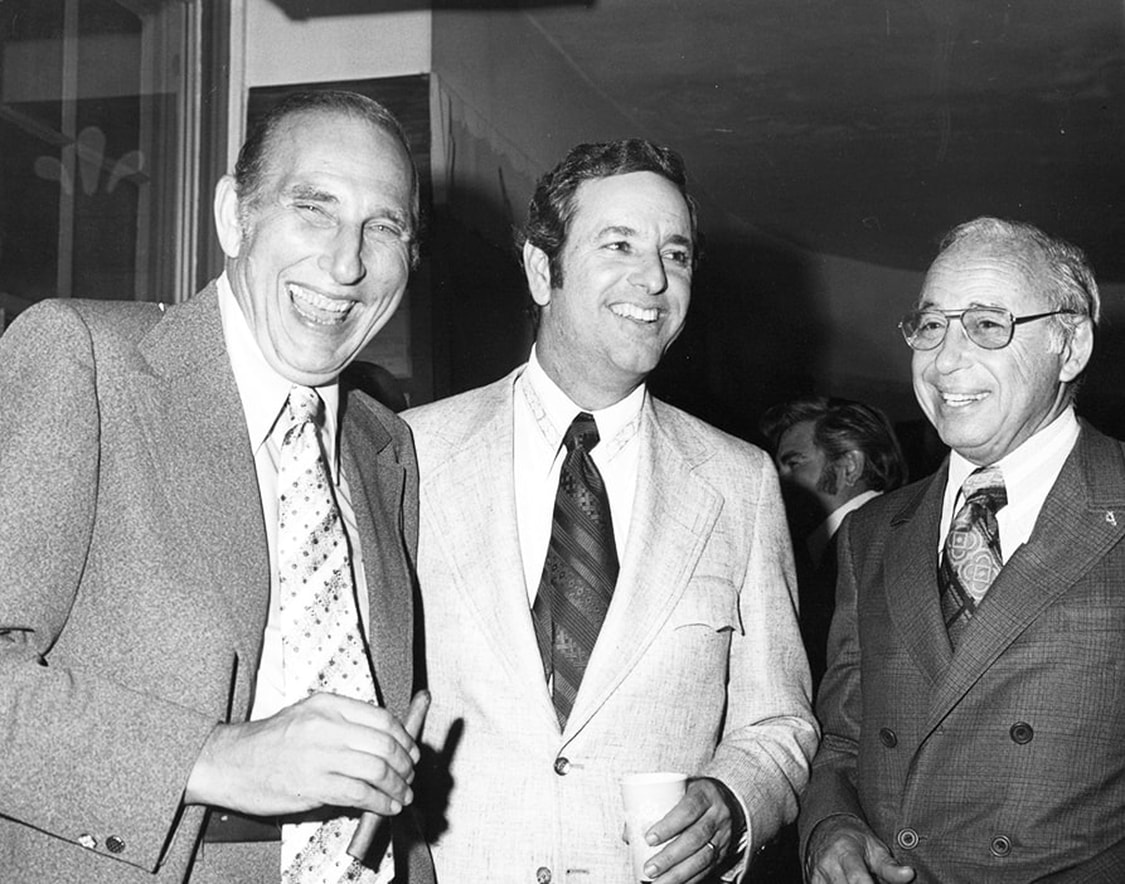

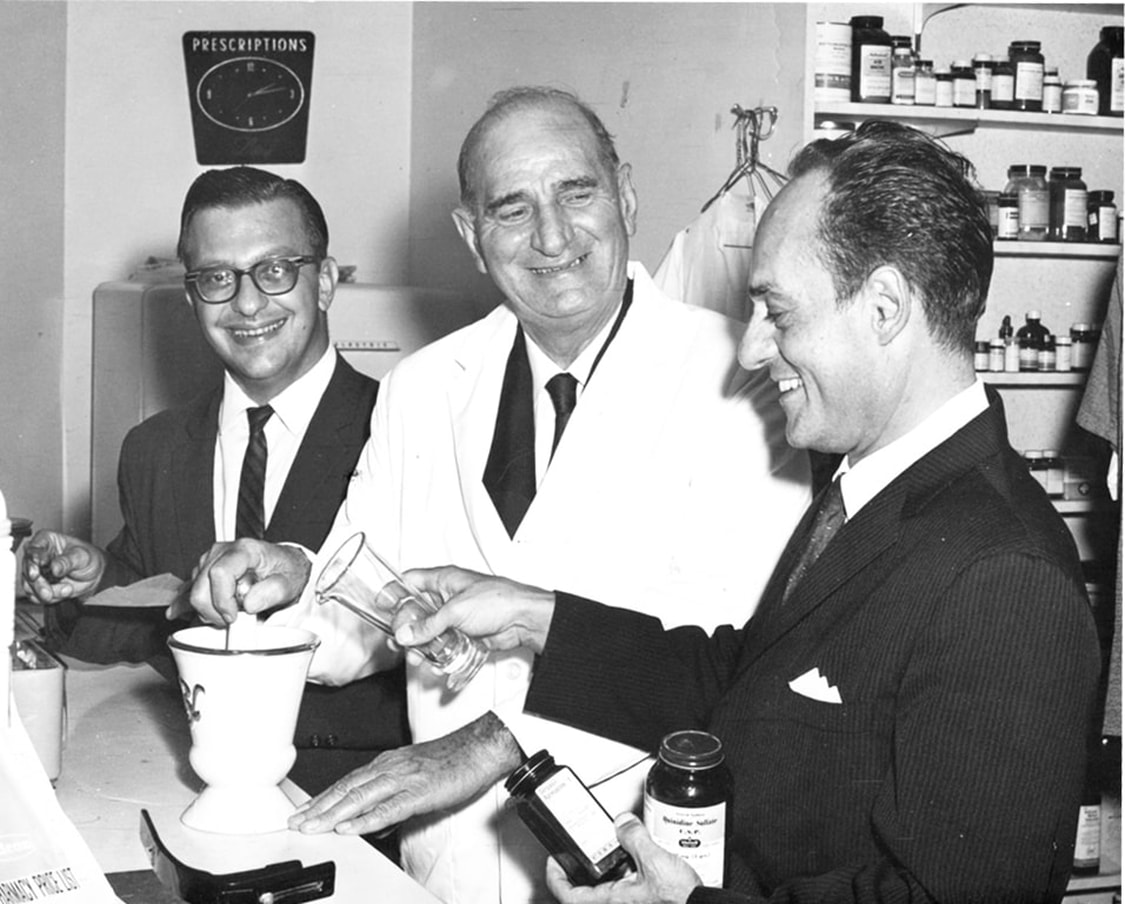

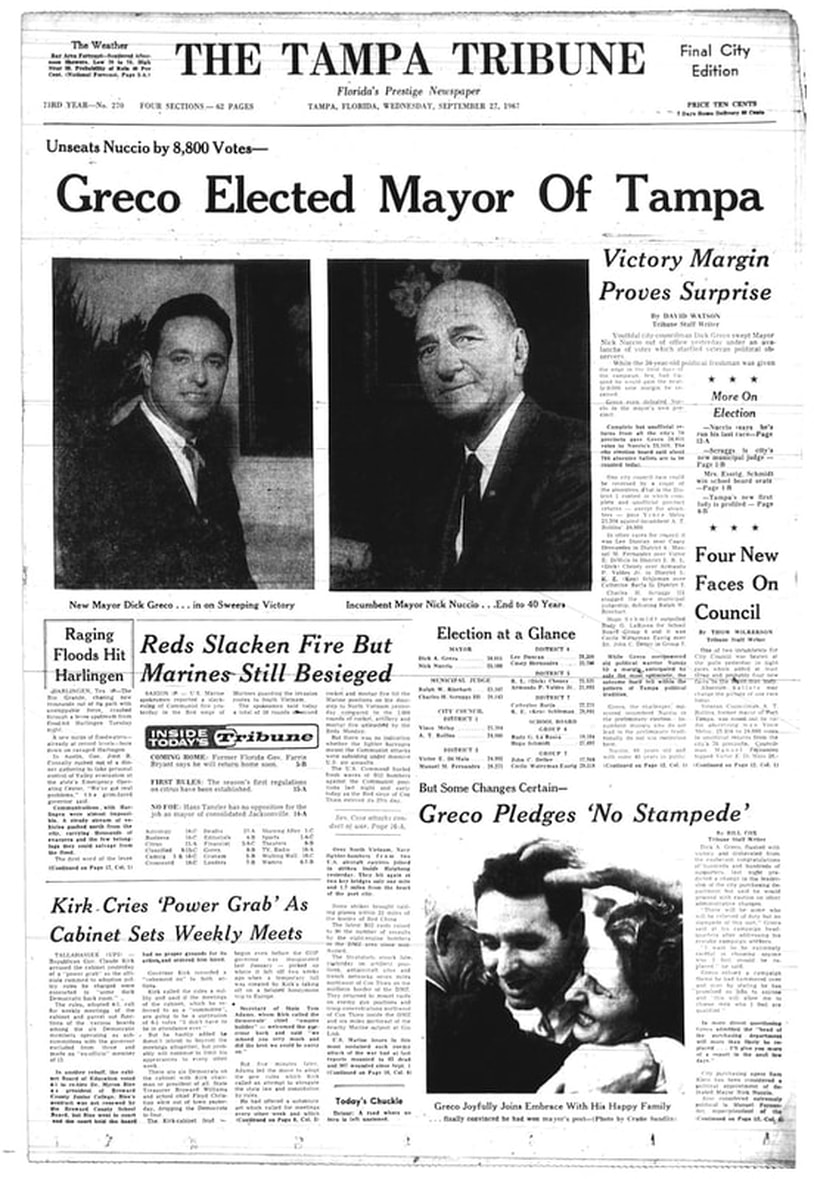

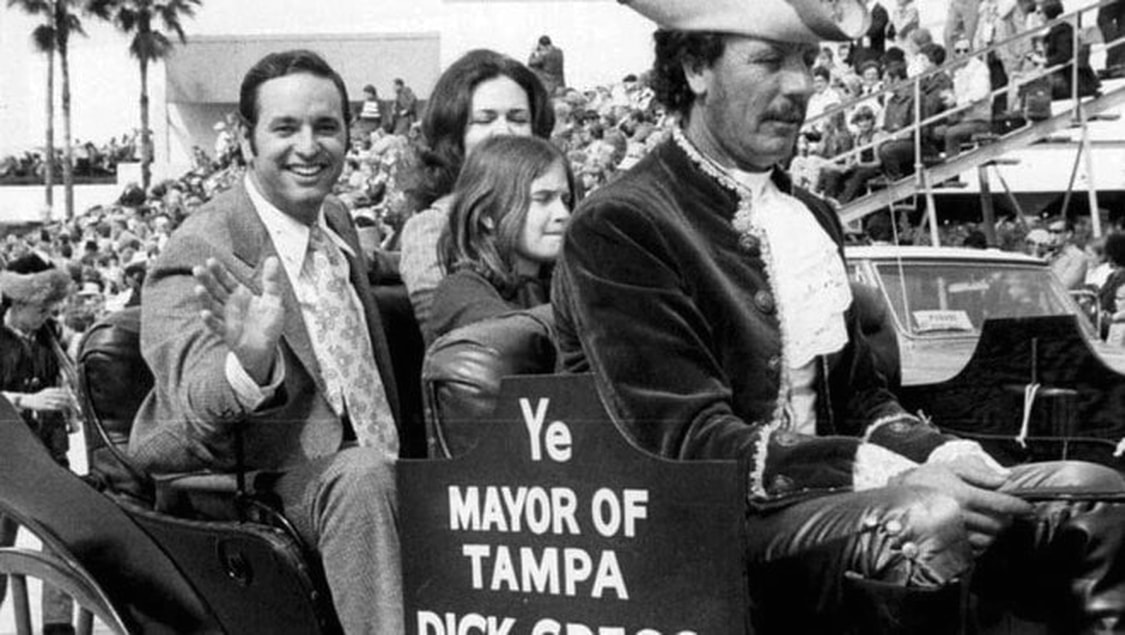

Long before Mayor Dick Greco was attempting to become the oldest Mayor in the history of Tampa, he was the youngest. Before he boasted of the experience he would bring to the mayoral position, he was the mayor with little experience. Before he was a political legend with his own statue, he had to defeat a political legend that was posthumously honored with a statue. Before he became Mayor Dick Greco, he had to defeat Mayor Nick Nuccio in the 1967 mayoral election, one of the hottest elections the city of Tampa has ever seen, an election that billed the young, handsome upstart against the old political legend. It was a heavyweight battle that changed the history of the city of Tampa forever. And it was a battle that started in 1963 when Mayor Dick Greco was known as City Councilman Dick Greco. A few days after Greco was elected city councilman in 1963, Nuccio visited Greco at home. He brought Greco's children gifts and then played with them for an hour. When Nuccio was finished entertaining the children, he put his arm around Greco, and the two talked politics, Nuccio sharing his years of experience with the new city councilman. Nuccio had an affinity for the young Greco. The two men shared a lot in common. They were both sons of first-generation immigrant Sicilian fathers who settled in Ybor City. And they both were outgoing, colorful individuals–the type of men who could walk into a room of strangers and walk out hours later with a room full of best friends. For these reasons, Nuccio wanted to groom Greco to help him understand the political process so that he could also enjoy a long career in public service. Before Nuccio left, he told Greco if he ever needed advice or a favor, all he had to do was ask. Greco would have been foolish not to take Nuccio up on that offer, as Nuccio was a political icon in Tampa. Born in Ybor City in 1901, Nuccio was the son of Sicilian immigrants who were among the first to populate the Latin community. He dropped out of high school to work in the shipyards during World War I to help support his family and later worked in real estate, insurance, and as a clerk in the Ybor City post office. The outgoing Nuccio never met a person to whom he couldn't talk, and these careers provided him with countless opportunities to meet new people and make new friends, making him one of the most well-known individuals in Ybor City. This popularity helped him launch a political career in 1929 as the Tampa City Councilman representing Ybor City. In 1937, he was elected to the Hillsborough County Commission and served seven straight terms. He often won fewer precincts than his opponents in the elections, but his support in Ybor City spurred high voter turnout in the district, which was enough to propel him to victory each time. Then, in 1956, he successfully ran for Mayor, becoming the first Latino to hold the city's top political post. He again won fewer precincts than his opponent, J.L. Young, but received almost every vote in Ybor City and Tampa's other Latin community–West Tampa. It was understandable why the Latinos supported him in such a manner. Not only was he a member of their community and a fellow Latino, but he went above and beyond the call of duty to support anyone in need. For instance, when he was a county commissioner, if a constituent from a rural section of the county was ill, he was known to accompany a physician to the constituent's home in the middle of the night to ensure the doctors could locate unmarked rural roads. As Mayor of Tampa, when a Ybor City resident told Nuccio that his daughter was suffering countless asthma attacks triggered by traffic on his shell-paved road, Nuccio had the road repaved within 24 hours. Throughout his political career, Nuccio focused on improvement projects in less fortunate neighborhoods–repaving streets, cleaning up parks, laying sidewalks, and installing benches. He also pushed for the construction of libraries, bridges, fire and police stations, public pools, and parks–and Nuccio engraved his name on every public improvement project he spearheaded. For decades, the name Nick Nuccio was visible on sidewalks, park benches, seawalls, and every piece of concrete laid by his administration so that everyone would know the good he was doing for the community. By all accounts, Nuccio was a tremendous mayor, one of the greatest the city ever had, but as times changed, he did not–a fact that was hurting the city and that Greco learned firsthand in 1965. In early 1965, a dozen low-income housing residents wearing tattered clothes over their wilting bodies visited City Councilman Greco at his family's hardware store in Ybor City, begging Greco for help. They explained that they lived in a trailer park on a plot of land on the Hillsborough River that the city deemed too valuable for low-income residents. City leaders had big plans for that plot of land and were telling the residents to vacate within a few months so that they could begin construction of the city project. The residents had nowhere else to go, though. They were 75 years old and older. They didn't have jobs, nor did many of them have family to look after them. The low-income trailer park was all they could afford. They explained that it would take them longer than a few months to find new dwellings, pick up their homes, and start their lives over somewhere else. With tears in their eyes, they begged Greco for help; they begged him for more time. He promised to do all he could to give them more time and told them he would take their issue right to Mayor Nuccio. The following day, he visited Nuccio at his regular morning spot–Cuervo's Café in Ybor City–and told the mayor the sad story he'd heard a day earlier. But Nuccio did not provide Greco with the answer he was looking for. Lighting a new cigar, Nuccio chuckled, leaned back in his chair, took a sip of his Cuban coffee, and, according to Greco, told him in a grandfatherly manner that he had a lot to learn about politics. Nuccio explained to Greco that no matter what the city does for those older people, they will be angry because they will have to move sooner or later. He told Greco that if the city gives them another year or so, they will still be living in Tampa when Greco is up for reelection. Nuccio told Greco that his opponent would surely make them an empty promise that he could prevent the city from moving them, painting Greco as the bad guy for only being able to promise a delay in their move. So, concluded Nuccio, the right political move is to displace these people immediately and hope that most of them leave Tampa altogether so they could not vote for Greco's opponent. "He said never leave that many people in one spot who hate you," remembered Greco. "And I thought, my God, I've never looked at politics like that, nor would I ever. But that's how he thought, and it was disheartening. I did learn a lot from Nuccio. At that point, I realized that the city needed to change. We couldn't continue to run in such an old-fashioned manner." Greco realized that some Tampa politicians were focusing too much of their resources on winning over the loyalty of their constituents rather than doing what was right for the city. For all the good Nuccio had done over the years, he had lost sight of what was most important. He was putting his own success above the city's success. For instance, Greco said, under Nuccio and previous mayors, if a neighborhood wanted a streetlight fixed, they had to petition the mayor’s office, who would then tell Tampa Electric to fix it. Or if a neighborhood had a pothole that needed to be fixed, the residents petitioned the mayor’s office, who would then tell the road department to fix it. By doing so, Greco explained, every neighbor who signed the petition felt that the mayor fixed their problem because they personally asked the mayor to do so. When the next election came, every person who signed a petition and had their problem remedied would vote for the incumbent because they felt a personal connection to the mayor. This created several problems, explained Greco. First, it gave the constituents a false sense of the workings of government. Streets should be repaved, streetlights fixed, and parks maintained because that was the job of local government, something they should do without any prompting, not because someone petitioned the mayor’s office. Secondly, some city needs were put on the back burner in favor of projects that garnered votes. For example, a neighborhood with 30 voters that needed a pothole fixed may have taken precedence over a neighborhood with ten voters that needed a streetlight fixed to ensure the safety of its children. "And think of the patronage that he acquired by doing it that way over a period of time," said Greco. "My God, I'd go somewhere with him, and somebody would say they have a mess on their street, and maybe sometime that afternoon, it would be fixed. You do that for many years and think of the people indebted to you. No one ever realized it was their money; their taxes paid for these improvements, so they were entitled to it." This type of city planning (or the need for more planning) strains city resources. For instance, by paving roads according to request rather than systematically by location, a street on one side of the city may have been paved one day, and the following day, a street on the other side of the city may have been paved. Or a crumbling street may have been allowed to fall into further disrepair because not enough residents signed a petition, upping the cost to fix the road when it was finally tended to. These inefficiencies wasted time and money. It would have been more cost-effective to come up with a comprehensive plan and fix streets in order of their location and need, which would allow the city to move the equipment slowly, from one block to another, rather than wasting man-hours cleaning it up so it could be moved across the city. While he was a city councilman, the more Greco dug into how the city was run, the more dismayed he became. For instance, one morning, Greco read in The Tampa Tribune that the city would spend $3 million on capital improvement projects that the City Council was never told about or allowed to approve. The city is supposed to work off checks and balances, but Nuccio had bypassed the process. On another occasion, Greco learned that Nuccio approved $289,276.89 worth of purchases from two companies without seeking outside bidders. Greco said that Nuccio never looked for the best deal; he gave the money to companies that had supported his election. Greco said that he tried to tell Nuccio and the other members of the City Council that policies needed to change, but his words fell on deaf ears. Tampa was a small city on the brink of becoming a major city, but its small-town thinking prevented it; major corporations would not move to a city with an old-school mentality. If major corporations would not relocate to or open offices in Tampa, it would never grow and would always be a small mom-and-pop cow town. Greco knew things would only change when new blood sat in the mayor’s office. "But it wasn't just Nick Nuccio who did things like this. It was every Mayor that had ever been there," explained Greco. "It wasn't that they were trying to be bad or ugly. That's just the way it worked. That's just the way they knew." When the next mayoral election drew near, Nuccio announced that he would not run for reelection and that he would retire from politics following his term. Greco thought this opened the door for new blood to sit in the mayor’s office and make the changes necessary for the city to grow, but primarily old blood candidates–men who had been part of the system for too many years to have the ability to make changes–threw their hats into the ring. Even though Nuccio would be gone, the old system would remain unless a young man jumped into the race. Greco decided he would run. "A lot of people thought I was too young when I announced," said Greco. "But I decided I needed to do it. I could either sit back and complain or stand up and do something." As the mayoral election drew nearer, its dynamics suddenly changed. Nick Nuccio decided he would run after all, and many political pundits predicted that Nuccio would run away with the election. Greco would not bow out, though. Greco loved Nuccio, but he said he loved the city more and knew that the only way Tampa could fulfill its potential and become a major metropolis was to get new blood into City Hall. Nuccio continued to govern Tampa as though it was the 1930s, not the late 1960s. In the late 1960s, a city had to be run like a corporation, not a mom-and-pop store. And with the problems the city faced, it needed a leader with an abundance of energy; it needed a young man. "Everything changes in life," explained Greco. "The old way of doing things wasn't wrong, but things needed to evolve." If Greco were going to become the next Mayor of Tampa, it would be challenging. He had an uphill battle in front of him. His opponents were all qualified. Besides Nuccio, the election also included Rudy Rodriguez, a 13-year veteran of the County Commission; Doug West, a 15-year veteran of Tampa City Council; and Tampa businessman Jim Fair. Greco was just 33 years old (34 by the time the election was over), attempting to become the youngest Mayor of any major city in the history of the United States; many voters saw his age as a deterrent, and his opponents painted him as a kid, someone without the experience necessary to run a major city. Greco would not allow his age to become a negative. Instead, he made it a positive. He reminded the voters that the old-school thinkers were the ones who led Tampa to that bleak point in its history, and he told voters new blood was needed to lead Tampa into the future. To accentuate this point, rather than surrounding himself with political veterans to offset his lack of experience, he surrounded himself with other young men who, like Greco, were tired of the old political machine holding Tampa back and wanted to do their part to help shape the city. Seven men in particular made up his inner circle: stalwarts from his City Council election–Gary Smith, Chuck Smith, Jack Fernandez, and Minister Earl Hartman–were joined by Dr. Henry Fernandez, an optometrist with an office around the corner from the Greco Hardware Store and a man with connections to numerous civic organizations; Jack Overstreet, a neighbor and member of Greco's church; and George Levy, a longtime friend of Greco's then-wife, Dana, and owner of a successful trophy shop. Their election plan was to demonstrate through their campaign how Greco would run the city–with excitement and efficiency. The seven men split the city into districts–Chuck Smith and Gary Smith took the north side, Levy took the south side, and so on. Greco's seven prominent men assembled and led teams in their respective districts. They made friendly wagers on who would draw the largest crowds to their campaign events, sign up the most volunteers, and hold the most parties in Greco's honor. And Greco never missed a party or event, sleeping an average of three hours a night during the campaign. "Dick was in charge," said John Fernandez. "He made sure we had somebody covering every corner of the city. And before we knew it, we had a well-orchestrated grassroots campaign. And it just started to mushroom." When there wasn't a party to attend, Greco and his campaign team held their own impromptu parties, meeting at a downtown bar near their campaign headquarters to discuss the election. They were Tampa's political rat pack. "Bill Cox of The Tampa Tribune liked to come to the bar with us," said Gary Smith. "He liked to be part of it and enjoyed watching us interact because while the campaign was run business-like–splitting the city up into districts and covering every foot of each district–we also had a lot of fun. And he ended up naming us the Magnificent Seven." As the legend of the Magnificent Seven grew, so did their volunteer support. The younger generation was driving Greco's campaign. Young men and women heard of the Greco campaign, of a group of dynamic up-and-comers who wanted to inject City Hall with a shot of youthful exuberance, who wanted to reshape the city and turn it into a thriving metropolis, who wanted to bring Tampa into the modern age, and who wanted to do it all while having fun, and they wanted to be a part of it. "We had a lot of parties, get-togethers, things that would get more young people involved," said Levy. "We were building a great organization, were having a ball doing it, and many of our volunteers were successful young men and women." "It was like the Kennedy generation," said Fernandez. "You know, young people were looking for something to excite them." Greco's wife added to the Kennedy comparisons. She was by his side for all public events, her style, glowing smile, outgoing personality, and grace comparable to the beloved Jackie O.'s. Greco didn't just talk and act like a worthy candidate; he looked like a natural leader. "Dick knew how to mix," said Fernandez. "That's one thing he could do. He could mix in a crowd, and before he was through, he would have spoken to everyone and made sure they were voting for him. And then the more people he convinced to vote for him, the more people he had helping him. We had such a large staff of volunteers it was overwhelming." But Greco never asked his supporters for money; he refused to ask for campaign donations, believing that doing so meant he would have to promise political favors in return for support. "I never wanted to owe anyone anything," explained Greco. "If I were going to win, it would have to be because I was the most qualified, not because I gave out empty promises." Not only did he not make empty promises, but he also made unpopular promises. He told the press that as Mayor, he would support new taxes if needed, stating that he favored additional liquor and cigarette taxes and supported a franchise tax on General Telephone Company, a tax he expected to pass on to the customers. Greco said he wasn't afraid to tell the truth. "I told people that if I had to raise taxes, I would, but I would explain why I was raising them so that you would understand." He even spoke openly about replacing some of the city's top officials, declaring that he would hire a new coordinator to oversee city spending programs and fire Tampa's police chief. "He has attacked patronage politics in police department promotions. A result of the practice is that several high-ranking police officers are active in a political club backing Mayor Nuccio," editorialized The Tampa Tribune on September 3, 1967. The lack of money and unpopular promises did not matter. While his campaign raised just $20,000 in cash, thanks to his supporters, he had no fear of losing the propaganda war. Supporters may not have been giving money but donated political paraphernalia–signs, balloons, bumper stickers, and t-shirts. They even had an airplane and helicopter in their arsenal, both provided free of charge by supporters. "I remember we knew where [former Mayor of Tampa] Bill Poe's beach house was, and he was supporting Nuccio, so we flew our helicopter with our signs over that area the weekend we knew he was there," laughed Levy. "When I saw him later that week, he said, 'Damn, I can't seem to get away from you guys. Everywhere I look, I see the name Greco.'" With so many in-kind services being donated to the campaign, Greco could use the money he had raised on political advertisements. He took out a four-page ad in The Tampa Tribune called "The Greco Record." The four pages were filled with positive articles The Tampa Tribune had written about him over the years and were designed to look like they were part of the newspaper, not a paid advertisement. He also utilized television better than his opponents, producing numerous commercials. "Most observers feel television will be Greco's top medium in the campaign," wrote Tampa Tribune reporter Bill Cox on August 28, 1967. "Greco, 34, is young, handsome, articulate, and projects sincerity." Greco also used the charms of his family to his advantage. "I remember doing two distinct commercials as a little boy for the campaign," said Greco's son, Judge Dick Greco Jr. "In one, I just said, 'Voting is a cherished right, so be a good American and go to the polls.' And then they'd flash 'Vote Greco' on the screen. And in another, I'd say, 'I'm Dickie Greco, and this is my father, and he is 34 years old,' and he'd walk out, and then my mother would walk out, and I'd say, 'This is my mother, and I'm not allowed to say how old she is.' People thought it was hilarious. It was all paying off. On September 3, 1967, The Tampa Tribune, which was the most important endorsement to win, officially endorsed the young candidate, echoing the speeches Greco had been giving for months: The Nuccio administration is still shaped by the old ward system political philosophy in which the mayor grew up. Do personal favors for people from public funds, obligating them for the next election. Spend the money where the pressure is most significant or where it will make the best public show. Channel every detail–whether it's installing a streetlight or hiring a garbage truck driver–through the mayor Tampa cannot afford to continue at City Hall the piecemeal planning and personal politics that encumber its progress–that permit an understaffed and under-equipped police force, a rebellious fire department, potholed streets, weed-grown parkways, an obsolete traffic control system, a shortage of recreational facilities and on and on. Tampa desperately needs a new vision from its government leadership to realize the potential conferred by its natural assets. For a new outlook at City Hall, we recommend to the voters a new Mayor–Dick Greco. On Tuesday, September 12, 1967, Greco received the most mayoral votes in the general election, garnering 16,359 votes to Nuccio's 13,581. By law in Tampa, a candidate needs 50 percent of the votes to win the election. If no candidate receives 50 percent, the two top vote-getters–Greco and Nuccio–compete against one another in a runoff election. Nuccio, fearing for his political life, came out swinging. "This campaign is now a new ball game! The voters have eliminated four of the candidates for Mayor. The issues are now quite clear. A young empty face versus an experienced head," La Gaceta Newspaper quoted Nuccio as saying in its September 16, 1967, edition. "In truth, his plans are nothing more than the empty words of some hidden editorial writer!" This was just the first of many attacks by Nuccio. With just two weeks to go and a large margin of votes to makeup, Nuccio stayed on the offensive. On September 14, 1967, the Tribune quoted Nuccio calling Greco "a young empty face, a paint salesman, a fence straddler, sticky, glib and gullible." He questioned Greco's qualifications, stating that he doubted Greco even ran his family's hardware store, as the Greco family contended. "He is only a salesman…a paint salesman," Nuccio told the Tribune on September 19, 1967. "Dun and Bradstreet lists the total worth of this corporation at $1,000, yet he wants to run a $50 or $60 million corporation." This was just the first of many attacks by Nuccio. Fernandez said Nuccio labeled Greco as a "silk stocking," a man who turned his back on Ybor City in favor of the South Tampa Anglo community. "It is now simply a question of whether the people will continue to control city hall or permit it to fall into the hands of the 'thought makers' who dwell in the Ivory Tower of the Tribune," wrote Roland Manteiga, publisher of La Gaceta Newspaper, on September 16, 1967. Manteiga was a close friend of Nuccio's. Greco not only started to lose the support of Ybor City, but he also became the recipient of some outright hatred. "I can remember, for instance, getting a call telling me not to show up to the Italian Club with Dick," said Gary Smith. "There was some luncheon with tea and dancing afterward, and we thought it would be a good place to campaign. I was warned that if we went, Dick would suffer bodily harm. They said this is our crowd, and he's not part of us. We went, and nothing happened, but we were always worried." Greco never seemed phased by the attacks. Instead, he took the high road, refusing to counter with equally insulting accusations, telling various newspapers in September 1967: "It is important that people know that it is possible to win an election while doing everything on a high level." "I feel sorry for him. He recognizes that he has problems, which is the only track he can take." "I won't turn the runoff for mayor into a dirty name-calling 'game' no matter what Mayor Nuccio says or does." "It's unfortunate that a man who's been in public life for 40 years can't stand on his own merits." "He has completely lost his cool. He can rant and rave forever, but I will not indulge." "Mudslinging, innuendo, and lies are appealing to some people. It typifies the old style of campaigning." By taking the high road, Greco was pulling away in the polls. It was a brilliant political move. If Greco was Tampa's Kennedy, Nuccio was its Nixon. The Tribune entered the act, lauding Greco while burying Nuccio on September 24, 1967. "It will be to the everlasting credit of the maturity and intelligence of Mr. Greco that although many men would have fallen for this old trick, he maintained his pledge to the people that the campaign for Mayor of the City of Tampa would not be turned into a 'political circus.'" But the nail in Nuccio's political coffin came during a televised debate on Sunday, September 17, 1967. Nuccio renewed his attacks on Greco, again claiming Greco was too young to be Mayor and that running a hardware store that is the business equivalent to a "hamburger stand" did not qualify him to be Mayor. Before the debate, Greco's campaign team handed him prepared comments to rebut Nuccio's remarks. Greco never read them. He returned the notes to his team and walked into the television studio, ready to speak from the heart. When it was Greco's turn to respond to his opponent, he smiled and looked directly into the camera so everyone watching at home felt personally addressed. "I said, 'I resent his attacks on my father very deeply, especially when there is such a contrast between the two men. My dad and my mother have always worked together all their life in that 'hamburger stand,' and they've made an honest living,'" remembered Greco. "And I then said, 'My parents raised me well with the money they earned from that hamburger stand, and they were able to send me to college. I realize the mayor wants to win very badly, which is why he is making such remarks, so I don't want anybody to think unkindly of him for his remarks. I forgive him for it, and I hope you do too.' And I left it like that on TV." On Tuesday, September 26, Dick Greco became the youngest man ever to become Mayor of a major city in the United States when he defeated Nick Nuccio by just over 8,800 votes–34,011 to 25,169. He even defeated Nuccio in his own precinct by 44 votes. Nuccio felt the defeat marked the end of his legendary political career. "I have no future," he told The Tampa Tribune on September 27, 1967. "I am satisfied I will not run for anything. It is the fate of politics. The people's will has spoken, and so far, as I'm concerned, it is final." Nuccio would run for Mayor again in 1971 and lose to Greco again. "Although the leaves did not come tumbling down this early autumn day, the furious Winds of Change swept out the old. And so, it came to be, on that clear, warm day, Tuesday, September 26, 1967, which darkened in the afternoon because of clouds and rain, the winds of change swept young city councilman Dickie Greco into Tampa's highest office. The people had determined a change was needed," lamented Manteiga in La Gaceta on September 29, 1967. "We believe that someday, Tampans will agree that Nick C. Nuccio was Tampa's greatest mayor." But the end of one political legend's career meant the beginning of another. As Greco's supporters crammed into his downtown campaign headquarters to celebrate the victory on September 26, 1967, following the election, Greco waited outside, huddled under a tiny umbrella that shielded him from a downpour. His supporters chanted his name, but he refused to enter until his grandfather arrived. When he did, they strolled into the campaign headquarters together. As the crowd exploded in cheers, Greco heard his grandfather Segismundo Cotalero exclaim to another gentleman, "My grandson is Mayor. I have now seen everything I could ever want to see." "My God, I will never forget that," said Greco. "Think about it. He came from Spain as a kid, worked like a dog, and never went anywhere. There is no way you can judge what that meant to that guy." At the beckoning of his supporters, Greco strolled to the platform with his family and gave his victory speech. "I am very happy and a very humble young man," the September 27, 1968, edition of the Tribune quoted him as saying in his victory speech. "The credit for this victory goes to you, my friends. This is a tremendous responsibility for a 34-year-old man. I accept it with enthusiasm." That day, Dick Greco ceased to exist, and Mayor Dick Greco was born. CIGAR CITY MAGAZINE- MARCH/APRIL 2011 Art & Photography Contributors: Hillsborough County Public Library, Tampa Bay History Center, The Florida State Archives, The Tampa Tribune/Tampa Bay Times, University of South Florida Department of Special Collections, Ybor City Museum Society, private collections and/or writer. PAUL GUZZOPaul Guzzo is a reporter for the Tampa Bay Times. He found the lost segregation-era all-black Zion Cemetery. His unique beat also includes the local film industry, Tampa history, professional wrestling, and the odd and unique people who make up this area. Guzzo has been a journalist in Tampa since 1999, including a senior writer for Cigar City Magazine and Tampa Mafia Magazine. In his younger years, he was an independent filmmaker best known for an award-winning documentary on Charlie Wall, Tampa’s first crime lord. FOLLOW CIGAR CITY MAGAZINE

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2013

Categories

All

|

Cigar City is a Florida trademark and cannot be used without the written permission of its owner. Please contact [email protected]

© 2021 Cigar City Magazine. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

© 2021 Cigar City Magazine. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed