|

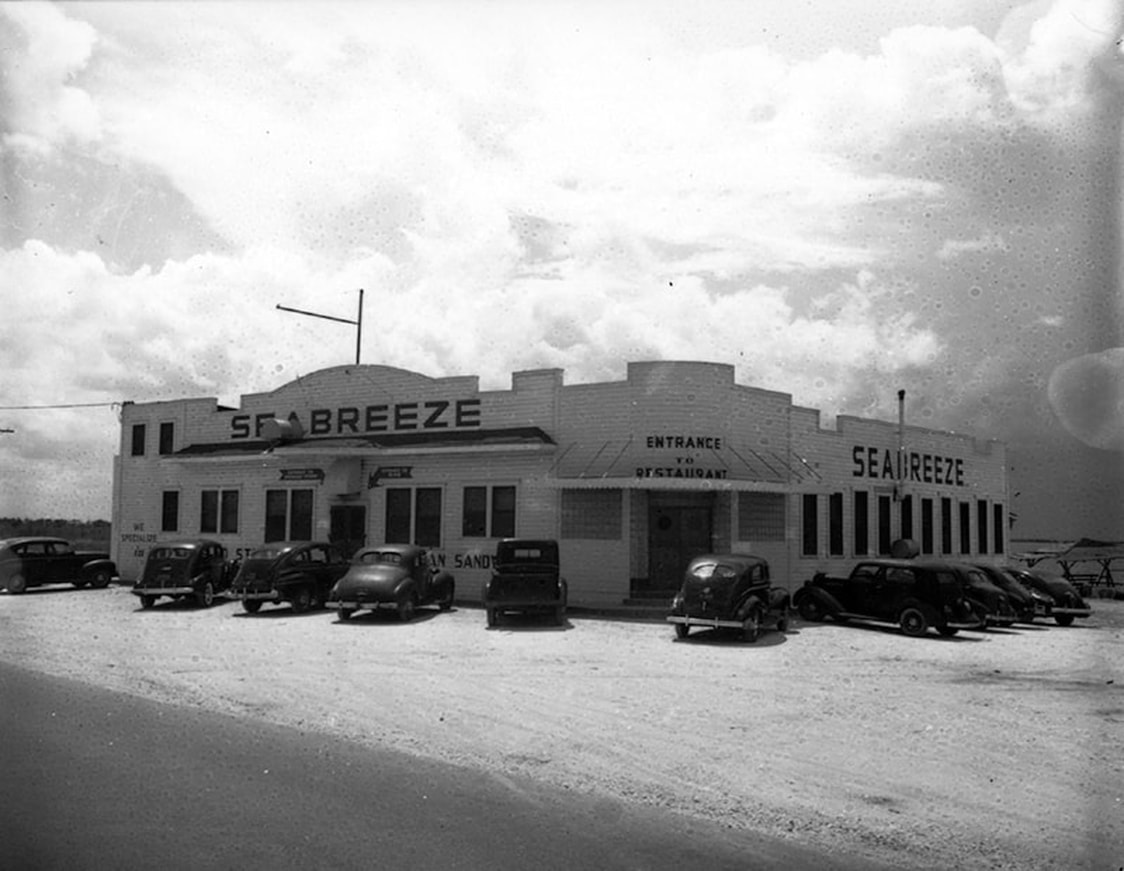

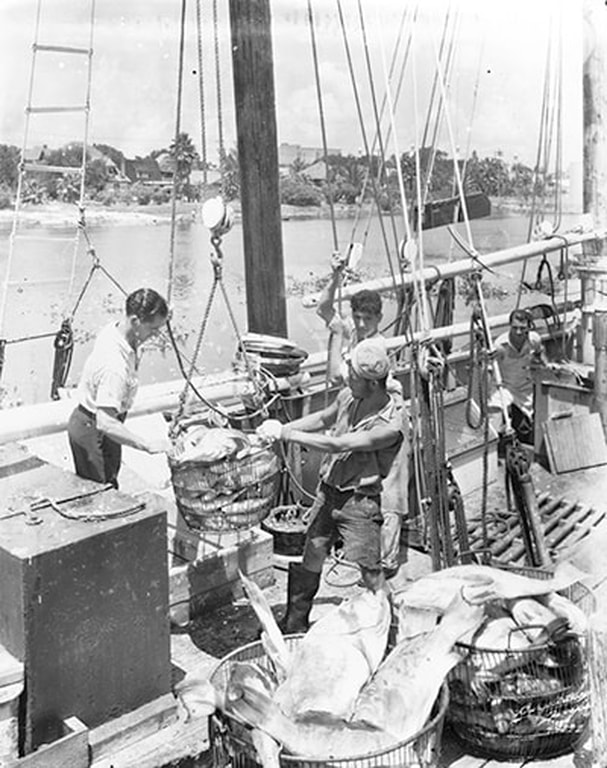

Eighty years ago, Victor Licata opened the Seabreeze Restaurant on the site, blending his beloved Italian cooking with Cuban and Cracker influences. The Seabreeze culled a blue-collar clientele from the workers of nearby industrial facilities. The Licata family arguably invented the deviled crab, a croquette spiked with spicy tomato sauce. Beginning in the 1960s, Robert and Helen Richards supplied the Seabreeze with seafood and later took over the business. Today, the restaurant is defunct, and a fishing family lost its livelihood. The price of doing business in Florida has climbed too high for most fishermen. Robert Richards and Helen Chattin grew up in Palmetto on the outskirts of Tampa. They went out crabbing one night as a first date. Helen shone the light and held the tub for their catch. During the 1950s and 60s, young folks ate, drank, and fell in love in the Seabreeze’s crushed shell parking lot. A temple of American drive-in culture, the restaurant’s good times and savory aromas drifted over the waters of the bay. Robert and Helen married in 1954. He worked as a roofer and boilermaker, but saltwater flowed in his veins. One day when Robert admired a tub full of live shrimp and learned they were caught in the bay, inspiration struck. “I got the bug then,” he said of his desire to become a commercial fisherman. After several part-time shrimp seasons, Tony and George Licata–Victor’s sons–told Robert they needed soft shell crabs for their Seabreeze Restaurant. The men had been friends for many years, so Robert agreed to help and built a seafood market beside the restaurant. By 1970, Robert went deep into debt to accumulate a fleet of shrimp trawlers, and the fresh seafood attracted crowds of customers. Only a family passionate about fishing could persist in such a career. For many years, Robert and Helen adhered to the same exhausting routine. Robert shrimped all night. Helen woke before dawn to make him breakfast and take the kids to school before putting in a day at the market. When she returned home with the kids, Robert woke, ate supper, and returned to the shrimp fleet. When he set out for the night, Helen put the kids to bed and rested while she could. By 1980, the couple had built a strong business and brought more family into the operation. Today, such a business is nearly impossible to start on the coast of Florida. Historically, the state’s business and political leaders valued profits over sustainability, and people like the Richards paid the price. Tampa’s sewage, dumped into the bay after being treated with a cocktail of bacteria-killing chemicals, disrupted sea life. Planes dusted the bay with deadly poison meant to exterminate nearby fire ants. A recurring series of chemical spills from phosphate plants and incinerators took a deadly toll on the bay’s ecology, bleaching sea grass and seafood. Last year, a phosphate company’s gypsum stack collapsed into the bay, perpetuating one of Tampa’s less savory traditions. Robert estimates the late 1980s as being a low point for the health of Tampa Bay. Richards maintains that overfishing was never a problem. Net bans missed the real problem entirely. Pollution rendered many fish infertile. Legislation favored tourist sports fishermen over commercial fishing. Robert said of politicians and their new laws, “They abolished the commercial fishing industry.” Sporting anglers blamed their lack of catch on the fishing industry, “even though the shrimp boats were not catching any of the fish they caught,” Helen said. New pressure came from inland. Industrial farm-raised seafood treated with preservatives and plumping agents filled the seafood cases of supermarkets, bypassing local fishermen and markets alike. In 1990, a new crisis struck. George Licata announced he would sell the Seabreeze, and the Richards would lose their base of operations. The Richards feverishly searched for a new home for their fleet and market. “We looked everywhere,” Robert said, among “the dwindling space that’s available on the gulf coast.” Waterfront development occupied most of the land. The remaining spaces commanded too high a price for consideration. Once again, the Richards risked all for their chosen profession and bought the Seabreeze. They passed the market and fleet to their eldest son Jimmy. This preserved their beloved fishing business and made them restaurateurs, which they knew little about. George Licata promised to teach them the ropes of the Seabreeze after a vacation. He died of cancer soon after. The couple endured “much worse of a grind after taking over the eatery,” according to Helen. When asked if they considered selling out, Robert laughed and said, “As soon as we bought it!” It soon became apparent that neither the restaurant nor the market could prosper independently. At the market, young Jimmy Richards struggled. “As hard as he tried, he couldn’t make a go of it,” Robert said, “even though we had five boats then.” The catch slumped with the health of the bay and gulf. “As production declined in the seafood industry,” Robert explained, “instead of selling a lot of the products wholesale, our son would bring it to the restaurant, process it there, and sell it at a profit.” Robert and Helen welcomed the reliably fresh seafood. New laws prohibited them from buying products from fishermen who did not have expensive permits. The Richards became wary of unscrupulous wholesalers who marketed questionable products at premium prices. “Robert had to watch it constantly,” Helen said of their wholesale purchases. Jimmy’s fresh seafood allowed the Seabreeze to maintain quality without raising prices. Robert showed understandable frustration when he recalled that commercial fishermen could not catch mullet under a foot long. “Now that the fishing industry’s all but gone, sports fishermen can catch those little finger mullets for bait. You can throw a bait net and catch two or three hundred sometimes. But we weren’t allowed to catch and sell them for food.” The Richards family squeaked by despite mounting pressure. Helen remembered, “We had a tiger by the tail; you couldn’t turn it loose.” A legal battle over the property with the Tampa Port Authority–still in litigation today–exacerbated the problems. Robert suffered a serious heart attack. By 2002, Robert and Helen had reached the end of their rope. “We couldn’t stand it another day,” Robert said, “We weren’t staying afloat anymore.” They sold the property to International Ship Repair, and searched Florida’s gulf coast for new property but found nothing suitable. Despite the hardships of the past, the Richards enjoy their lives in retirement. Helen wrote the charming Seabreeze by the Bay Cookbook (as did this author, American Printing, 2001) as a farewell to the restaurant. They might even be able to forget the disappearance of their livelihood if they could find buyers for their remaining fleet. Selling three shrimp trawlers to Florida’s vanishing fishermen is no easy task. CIGAR CITY MAGAZINE- JULY/AUGUST 2006 Art & Photography Contributors: Hillsborough County Public Library, Tampa Bay History Center, The Florida State Archives, The Tampa Tribune/Tampa Bay Times, University of South Florida Department of Special Collections, Ybor City Museum Society, private collections and/or writer. ANDY HUSEAndrew Huse works as a librarian who specializes in archives at the University of South Florida Tampa Library's Special Collections. He writes, speaks and cooks about history when he can. His past work includes the centennial history of the Columbia restaurant (2009) and his latest book is called "From Saloons to Steakhouses: A History of Tampa." (2020) With Noel Smith and Wenceslau Galvez, Huse also co-authored "Tampa: Impressions of an Emigrant," an annotated translation of a rare book from 1896. (2020) All of his books are published through the University Press of Florida. He also has a website along with his partners Dr. Bárbara Cruz and Jeff Houck called The Cuban Sandwich: A History in Layers FOLLOW CIGAR CITY MAGAZINE

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2013

Categories

All

|

Cigar City is a Florida trademark and cannot be used without the written permission of its owner. Please contact [email protected]

© 2021 Cigar City Magazine. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

© 2021 Cigar City Magazine. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed