|

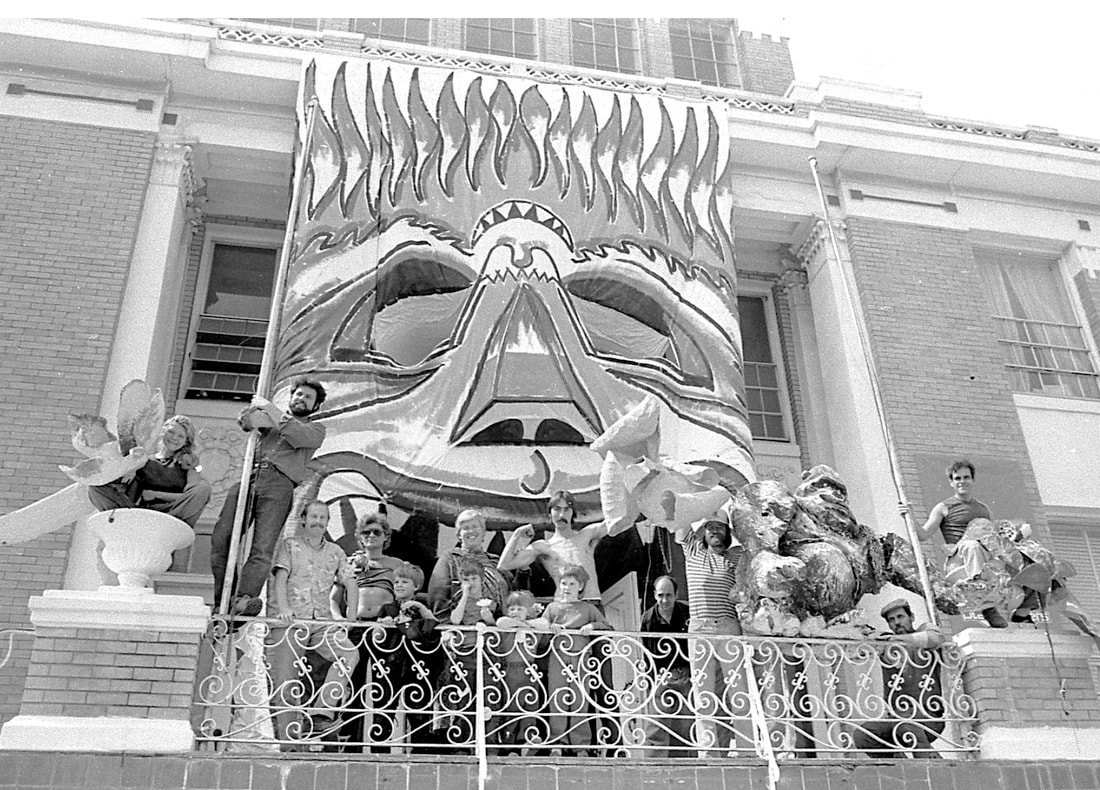

For many people, the history of Ybor City ends after the first few decades of the twentieth century, the cigar-making community's golden era. Following a series of devastating changes–the rise of mechanization and the decline of the hand-rolled cigar industry, World War II, government-driven urban renewal, and the separation of the district from downtown and south Tampa by an elevated highway and toll road–the once-vibrant community gradually emptied of residents and businesses. Stalwarts like the Columbia Restaurant continued, but Ybor grew to resemble a ghost town mostly until a new form of life filtered in. In the 1970s, artists began to discover the area's vacant warehouses and cigar factories. Social clubs of yesteryear, including the Cuban Club and El Centro Español, became ideal venues for performances by a low-budget theater company and all-night parties thrown by several artist collectives. Best of all, there wasn't much of anyone around to stop the artists from having fun. But the good times weren't destined to last long. Ironically, the success artists had to lure people to Ybor for various events led developers to envision–and, ultimately, to build–a commercial entertainment district in the 1990s. But from the short-lived cauldron of creativity sprang forth a contemporary legend whose legacy still haunts its creators today. Despite its relative youth, the yearly Halloween Street festival and parade has survived and thrived to become as much a part of Ybor's culture as cigar factories and café con leche. As local artist and Hillsborough Community College Special Projects Manager David Audet remembers, in the late 1970s, a person could lie in the middle of 7th Avenue with little fear of oncoming traffic. Visitors to once-bustling Ybor were few and far between, but a handful of artists had made their homes along the district's main drag. At the time, a young film and photography student at the University of South Florida, Audet was part of a cluster of urban pioneers who braved strange surroundings east of Interstate 275 in search of low rent and a small-town atmosphere. Audet called a second-floor apartment above the current site of King Corona (on 7th and 15th Street) home. Bud Lee, an award-winning photographer, and transplant from New York City whom Audet idolized, lived nearby with his wife Peggy in a storefront, where passersby occasionally wandered in and tried to buy their furniture. Nearby, the painter James Rosenquist had a studio. Looking for a way to draw visitors to Ybor, the Lees, Audet, and a small circle of friends hatched the idea of a yearly party called the Artists and Writers Ball. A satirical costume ball, it would serve in part as an underdog alternative to Gasparilla's exclusive fêtes. Seizing the Cuban Club as the perfect party site, the group decorated the building's four floors and patio in the spirit of whimsical theme–Dante's Inferno the first year, Daughters of Bizarro, Little Calhoun's Hawaiian Circus for the Poor, Cowboys, and Indians in Love, and Bad Taste in Outer Space to follow–and instituted a minimal charge for entertainment and drinks. Traditionally, a pair of artists were crowned king and queen each year (often with little regard for gender), and roller-skating troops were invited to navigate the Cuban Club's stairs. From the first year in 1976, the attending crowds quickly grew into the thousands. "Ybor was still quiet enough that you could have a great party there, and you weren't disturbing too many folks," explained Paul Wilborn, then a Tampa Tribune reporter and musician who was part of the group. "Those were the days before people learned about risk management," Audet said. What little money the group took in from ticket sales–almost always less than they had put into the party–they pumped back into a low-budget journal called Tabloid or invested in the following year's ball. Few of the artists in the group had a head for money. Without the help of one pragmatic personality, particularly Beverly Coe, Rosenquist's long-time assistant, practical concerns would have overwhelmed them, Peggy Lee recalled. Even with Coe and Audet at the helm, the crowds grew each year until the event became more than the group could handle. (After one particularly wild year at the Centro Español club, they vowed to limit the party's size to the Cuban Club's smaller digs.) They threw more than a dozen Artists and Writers Balls before the practice fizzled, but the idea had caught on, and other artist groups in the area began to throw parties, too. One such group, El Sama, was renowned for its yearly Halloween bash. "I look back, and I think: Were we insane?" Peggy Lee said. "None of us were in it for the money. That's for sure." Where the artists saw an excuse to have fun, business community members saw a golden opportunity. In 1985, Mike Shea ran Rough Riders, a bar and restaurant known as a watering hole for artists in Ybor Square. Shea's father-in-law was interested in the former V.M. Ybor cigar factory (at 8th Avenue and 13th Street) that publisher Harris Mullen had purchased and renovated as a retail complex in the 1970s. Shea arrived as property manager and soon took on the presidency of Ybor's cash-poor Chamber of Commerce. In search of a fundraiser for the Chamber, he envisioned a more ambitious version of the artists' parties for which the area had developed a reputation. At about the same time, El Sama decided to end their yearly Halloween party, and Shea saw an opportunity to start a tradition that could benefit the community. What Shea wanted to do was take the Halloween party to the streets. He had seen the Doo Dah Parade, a yearly march held in Pasadena to parody the Rose Parade, and a similar parade in Coconut Grove; he'd also been impressed by Key West's Fantasy Fest. With the audacity of his artistic predecessors and a dash of business acumen, Shea began to develop the idea of a satirical Halloween parade for Ybor City. He convinced Wilborn of the Artists and Writers group to join him. He also approached Steve Otto, a Tampa Tribune columnist who had dubbed Tampa the "Big Guava," à la the Big Apple. Shea told Otto he planned to call the event Guavaween and asked the columnist to serve as the "Not-So-Grand-Marshal." Skeptical but charmed, Otto accepted. As support mounted, Shea approached the city of Tampa and then-mayor Bob Martinez for approval and racked up a few sponsors for the event. In a move meant both to lampoon and pay tribute to Ybor's rich historical roots, Shea and company now a group that included members of the theater company Playmakers, who became, along with the Ybor Chamber, recipients of any proceeds from the event invented a mock mythology for the event. They invoked the (true) story of Gavino Gutierrez, a Cuban importer who came to Tampa hoping to start a guava jelly, paste, and preserve business. (Finding the area's land unsuitable for guava cultivation, Gutierrez recommended it to his friend, Vicente M. Ybor, as a site for his cigar-rolling factories.) Seizing on Ybor's little-known guava heritage, the group envisioned an immortal heroine to complement their theme: Mama Guava, a 1980s version of Carmen Miranda resplendent in a green, guava-studded leotard. Shea hired Kathi Grau, a local actress and drama teacher, to play the fruity temptress, a role she still reprises with gusto. Otto took to his parade marshal role, eventually earning him the title of Papa Guava in a brown bathrobe purchased from La France, a vintage clothing store in the district. "The first year, they gave me a donkey," Otto recalled. "It was really more of a burro. I told them, I can't ride this thing-it ought to ride me. Instead, I tried to pull it down the Street, and it ate about half of my bathrobe. Started getting pretty risqué there about halfway through." To the surprise of everyone involved, on the day of Guavaween's inaugural 1985 run, several thousand people showed up to line 7th Avenue. During the day, parents and children took part in costume and painting activities. Then, the night parade began. The floats came off without a hitch (more or less). Visitors ogled as a procession of wacky creations filed by a dozen blue-suited marlin trailed by a fisherman casting a net from atop a car, a truck bearing a "Human Black Bean," complete with carbon dioxide gas cloud; Our Ladies of the Perpetual Fruit; the Joe Redner School of Classical Dance; and the alcalde of Ybor City, Sam Leto in a black convertible. In the center of it all, Mama Guava rode atop a car guarded by polar bears (the mascot of the parade's beer sponsor), pelting the crowd with dried black beans. Following its first success, Guavaween enjoyed a few more good years, but the event soon developed a reputation that outshone its original artistic and satirical spirit. Thousands of attendees became tens of thousands, and businesses clamored to sponsor the event. Corporate floats replaced ingenious costumes, and the revelry became so intense that the parade route had to be fenced. Even the Chamber's promotional mailer included the phrase, "Show us your guavas," emphasizing the event's Mardi Gras-style abandon. In 1989, Otto called it quits as Papa Guava, saying the event had become too raunchy. Even Shea moved on, and the theater company Playmakers folded. For Guavaween's founders, the event had become something they never intended. Ironically, due to its success, change was afoot in Ybor. On the heels of the success of Guavaween and artist-run parties, Ybor began to look increasingly attractive to bar and nightclub owners. In the 1990s, the area slowly developed into a Bourbon Street-esque entertainment district. After a period of affordable rents and empty warehouses, property values rose too high for artists. Guavaween continued, though its rowdy image often led locals to shy away. In 1994, at the behest of then-mayor Sandy Freedman, the Chamber hired CC Events to oversee the event. Since then, the company, which has offices in Tampa and Ohio and touts Guavaween as one of its biggest and most beloved festivals, has worked to grow Tampa's best-known Halloween party while increasing its safety and improving its reputation. Now known nationally, CC Events' Guavaween still features a costume contest and daytime activities for families. Still, it also features national rock-and-roll acts on stages sponsored by corporate radio stations. With yearly visitors commandeering over 2,000 hotel rooms during Guavaween, the event has become a significant tourist attraction for the Historic District and the city. For the past decade, Ybor's movers and shakers have worked to transform the neighborhood from its adults-only entertainment incarnation to a mixed-use community with a solid small business and residential presence. Now the home of architecture and design firms, communications and film production companies, and a cluster of new condominiums, Ybor is beginning to thrive again, says Tom Keating, current Ybor Chamber of Commerce president. Even some of the artists are back. Audet, who has long been at the helm of the Ybor Festival of the Moving Image, will kick off a new literature and performance festival called Deep Carnivale: A Celebration of Words in September. Designed to attract a creative, multi-generational crowd, it harkens back to the spirit of Ybor's artsy days. Once more, change is afoot. Through it all, Guavaween-and the ever-youthful Mama Guava-lives on. Come October, listen for a rumble in the palmetto scrub, and don't forget your costume. NOTE: In 2012, the Ybor City Chamber of Commerce scrapped the annual Mama Guava Stumble Parade due to the challenging economic climate. CIGAR CITY MAGAZINE- SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2007 Art & Photography Contributors: Hillsborough County Public Library, Tampa Bay History Center, The Florida State Archives, The Tampa Tribune/Tampa Bay Times, University of South Florida Department of Special Collections, Ybor City Museum Society, private collections and/or writer. MEGAN VOELLERMegan Voeller is a Philadelphia-based educator, curator, and writer whose work focuses on critical intersections of contemporary art and health. She was previously the Curator and Art in Health Program Director at the University of South Florida Contemporary Art Museum, where she organized exhibitions and interdisciplinary educational programs, including observation training workshops for health professions students. As Visual Art Critic for the alternative newsweekly Creative Loafing, she wrote over 250 exhibition reviews and feature stories over a decade and has regularly contributed to other publications. Megan is a former co-host and freelance producer for WEDU Arts Plus, a public television program produced by Florida PBS affiliate WEDU. Click here to see more of Megan's work FOLLOW CIGAR CITY MAGAZINE

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2013

Categories

All

|

Cigar City is a Florida trademark and cannot be used without the written permission of its owner. Please contact info@cigarcitymagazine.com

© 2021 Cigar City Magazine. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

© 2021 Cigar City Magazine. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed