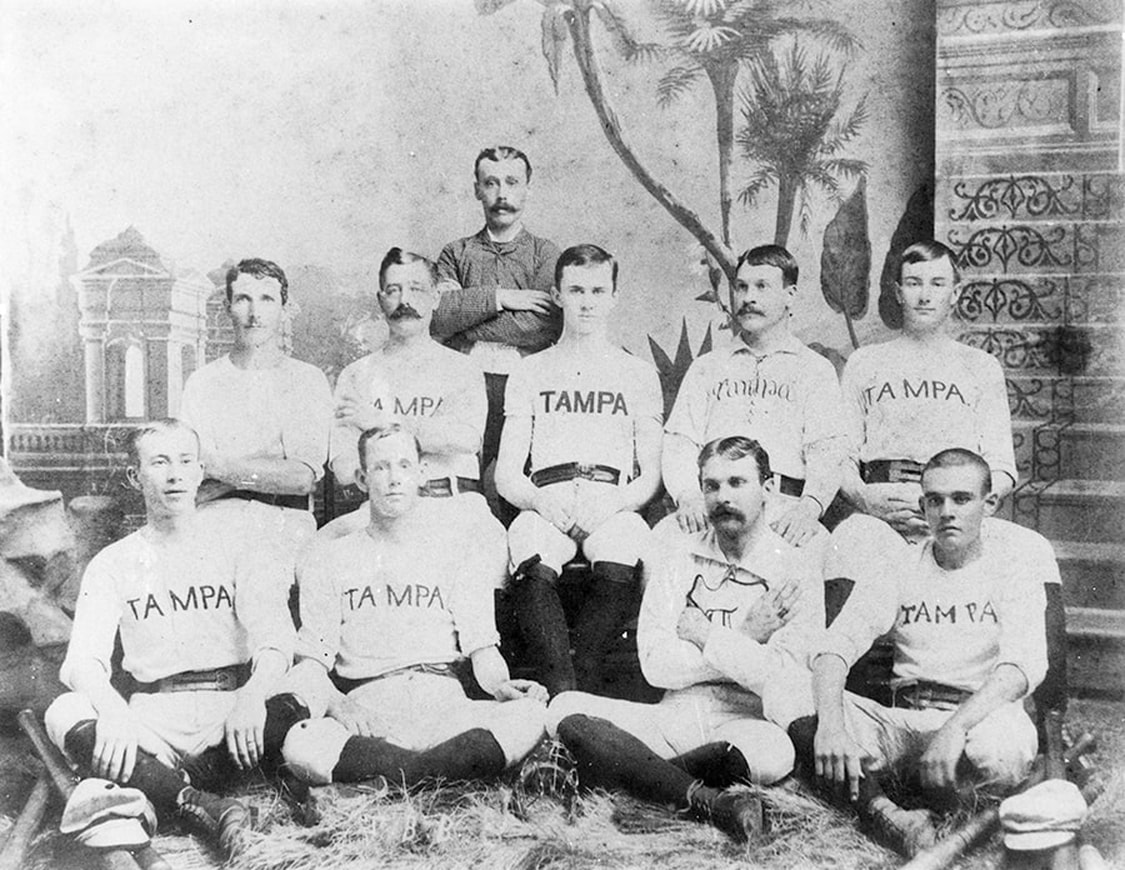

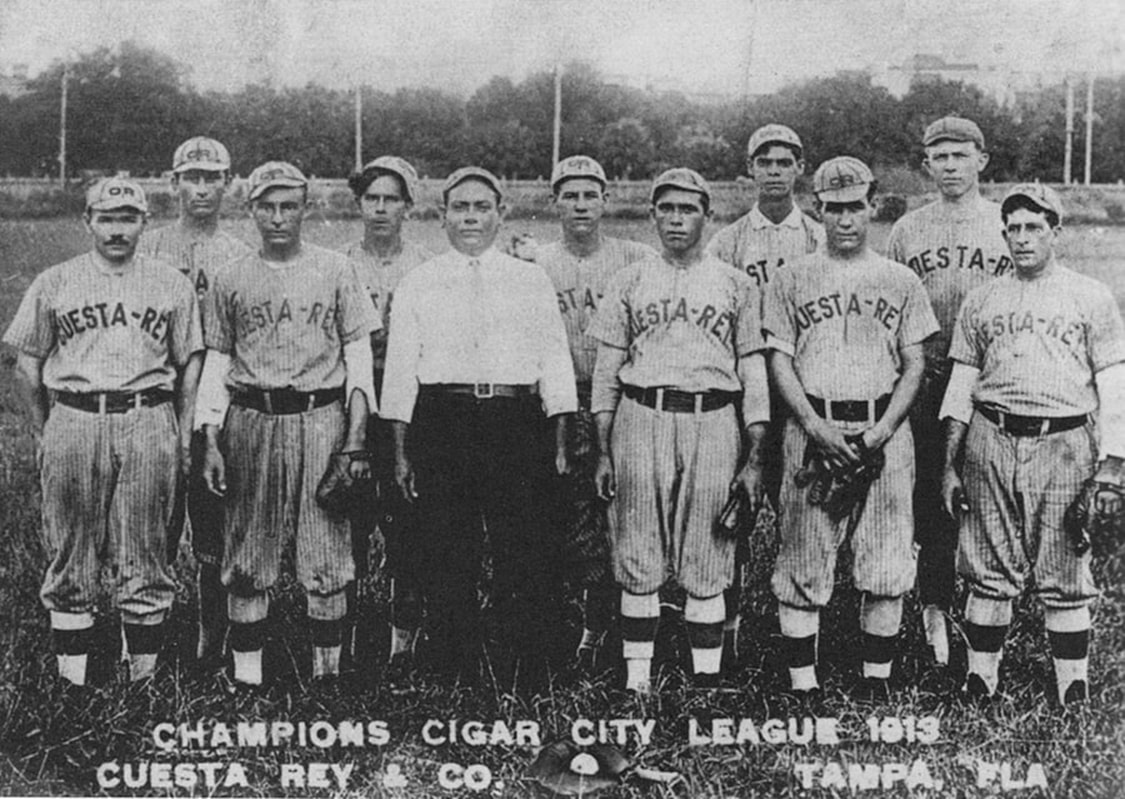

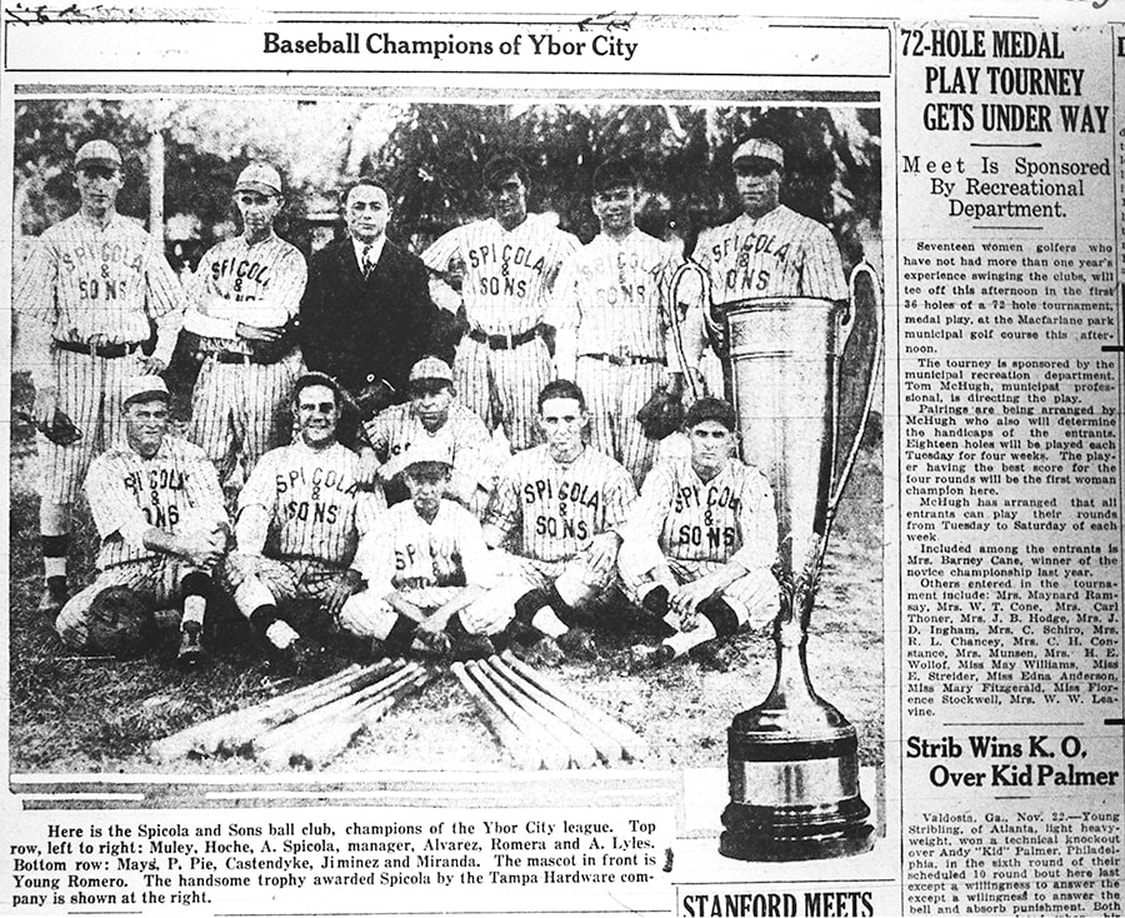

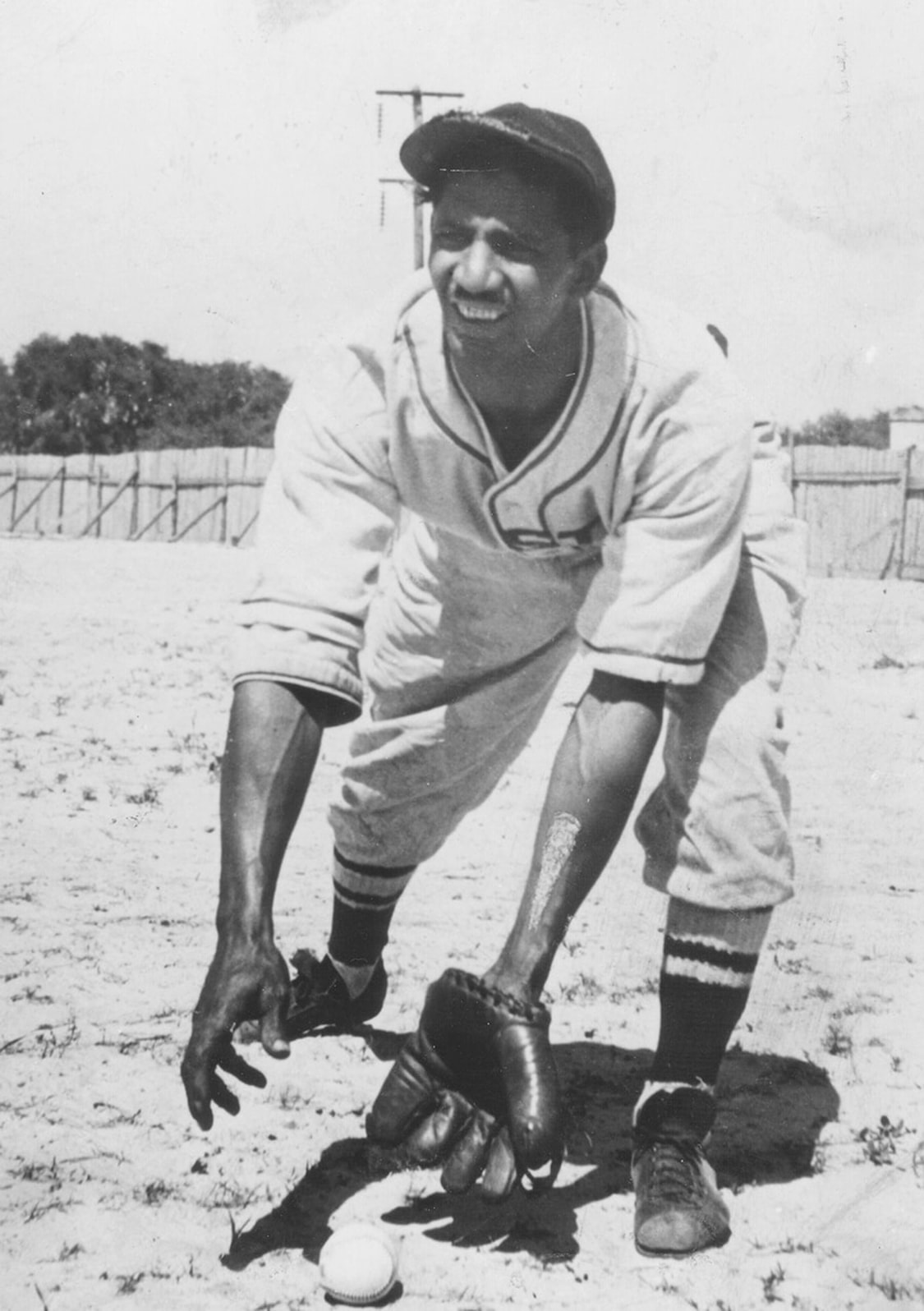

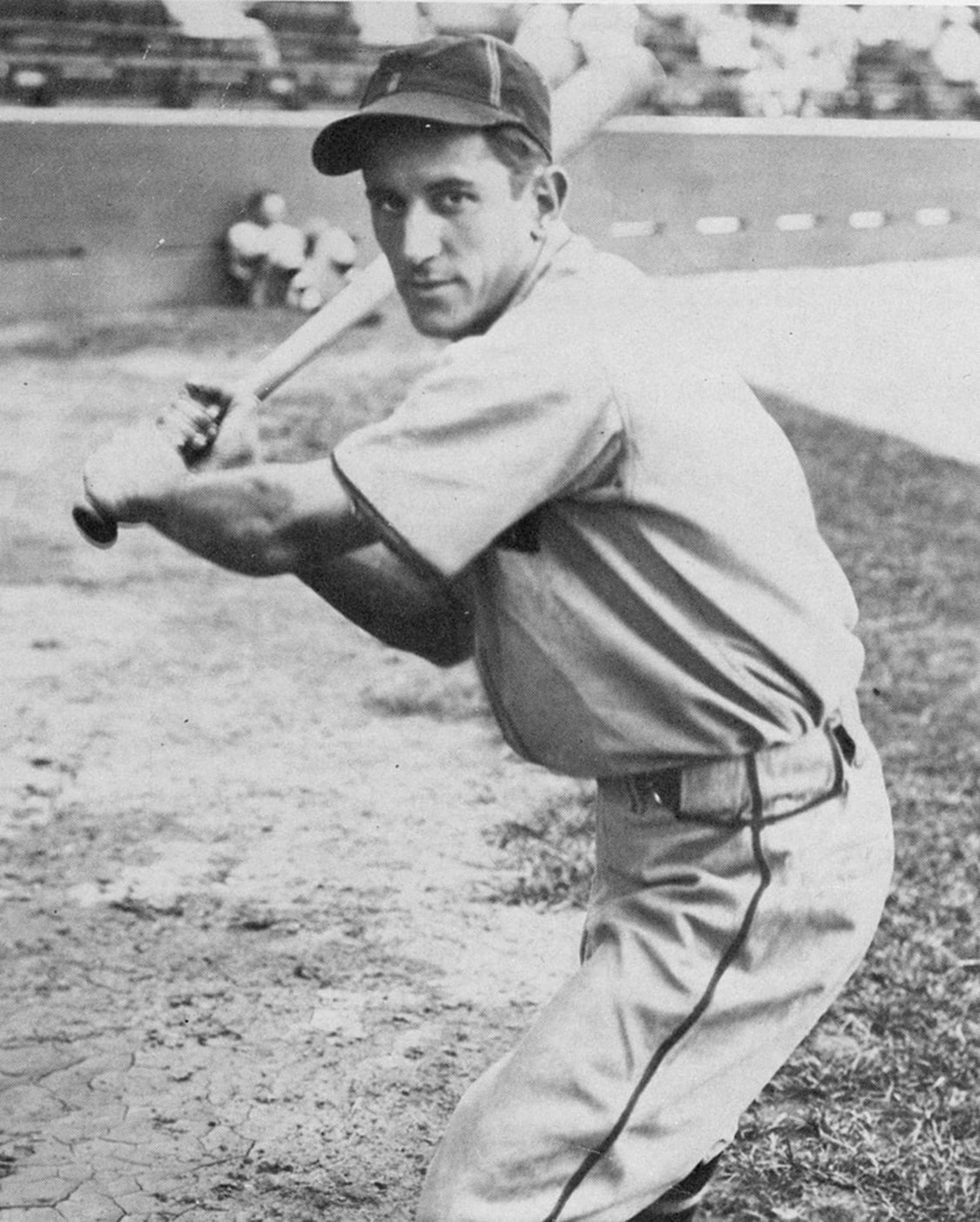

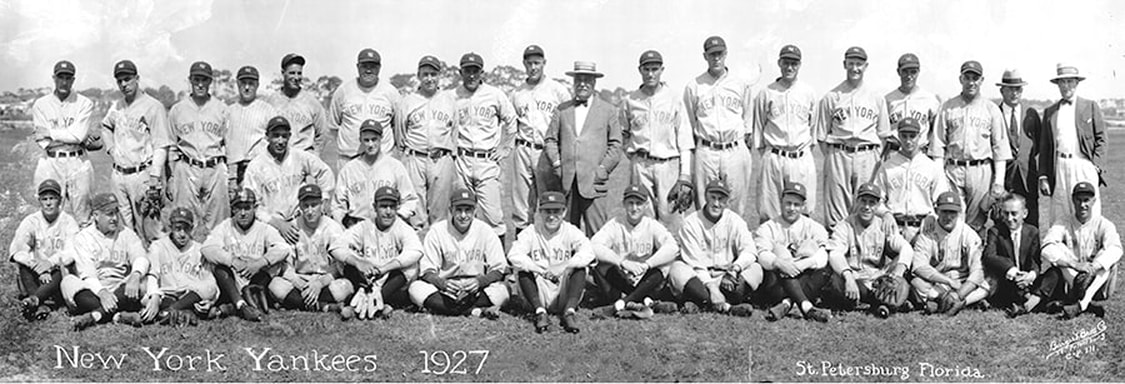

The Tampa Baseball Club of 1884-1885, winners of the South Florida Baseball Championship. Standing, center: Oliver Andreu, Secretary-treasurer. Top row, L-R: W.A. Legate, Charlie Livingston, John A. Jackson, J.A.M. Grable, E.L. Lesley. Bottom row, L-R, Ed Drake, J.C. McKay, B.A. Brown, Al Knight. The team members not present when the photo was taken were A.W. Cuscaden and George A. Bell.–Excerpted from the Tampa Daily Times, November 12, 1924. Early Beginnings Before spring training became the Florida mainstay it is today, baseball began taking root in the Tampa Bay area late in the 19th century. A.M. de Quesada's book, Baseball in Tampa Bay, notes how Union and Confederate soldiers brought the game to the Sunshine State when they returned home from the Civil War. Tampa had a team in the first short-lived Florida State League in 1892. Baseball's popularity in Tampa was also helped by a growing Cuban population, which came to work in the area's booming cigar industry of the late 1800s and early 1900s. Baseball had become popular in Cuba during the 1870s. As Cubans emigrated from Havana to Key West and then on to Ybor City and West Tampa, they brought a passion for baseball matched only in the United States. After all, the Professional Baseball League of Cuba began play in 1878, just two years after North America's National League was formed.  Cuesta Rey & Co. champions, Cigar City League, 1913. Cuesta Rey & Co. champions, Cigar City League, 1913. Luis A. Perez's 1994 article, Between Baseball and Bullfighting: The Quest for Nationality in Cuba, 1868-1898, points out that early Cuban baseball teams in Tampa were used in fundraising efforts for Cuba's anti-colonial revolution against Spain. For example, Julian Gonzalez's magazine, El Pelota, was a Tampa league's official donor, and sales profits were donated to the PRC, Partido Revolucionario Cubano. Tampa had its cigar factory teams in the 1910s, '20s, and '30s, with games played at West Tampa's Macfarlane Park. Local ethnic mutual-aid societies, such as the Círculo Cubano (Cuban Club), fielded teams as early as the First World War (1914-1919). By 1938, these ethnic clubs–Círculo Cubano, Centro Asturiano, the Italian Club, and the Loyal Knights Lodge–formed the Inter-social League. Games were played on Sundays at Cuscaden Park, bordered by 14th and 15th streets and 21st Avenue, just north of Columbus Drive in Ybor City. "The games always drew," Andrew Espolito, who managed and played in the league from 1939-1947, told The Tampa Tribune in April of 1990. "A crowd came out for every club. Rivalries were good." SEPARTE BUT NOT EQUAL But decades earlier, blacks in Tampa seldom could experience the rivalries of the ethnic society baseball teams. Jim Crow laws were in effect in Florida, and that was evident on the fields and in the stands, where "Colored Sections" were still in use at St. Petersburg's Al Lang Field as late as the 1950s. In her book More Than Black: Afro-Cubans in Tampa, Susan Greenbaum explains how the first act of the Afro-Cuban Martí-Maceo Society in 1900 was creating a baseball team, Los Gigantes Cubanos. But it never fielded the team. The other ethnic clubs and the large factories had teams, but Martí-Maceo "likely would not have been allowed to play white teams in Ybor City," Greenbaum wrote. Greenbaum also offers the example of Afro-Cuban baseball player Hipolito Arenas, born in 1907 in West Tampa, a year apart and one town over from Ybor City's Al Lopez. Arenas never played for the social club teams. Lopez, whose parents came from Spain and was white, was discovered during one of those amateur games. He would become Tampa's first Hall of Fame baseball player. On the other hand, Arenas played for a West Tampa neighborhood team of Afro-Cubans, who occasionally played against all-white social club teams. But the mixed competitions drew the attention of West Tampa police, who broke up the games. Arenas had no hope of being signed by "organized baseball." He instead toiled for 13 years in the Negro Leagues, making $150 per month at the end of his career, the same salary Lopez signed to play for at age 16 with the then-Class D Tampa Smokers. While Arenas never achieved the notoriety of Al Lopez, Afro-Cuban Alex Pompez, who recruited Arenas to play for a black minor league team, eventually received his just due with induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006. Pompez, who owned the New York Cubans of the Negro Leagues, grew up in Havana and Tampa. In 1910 at age 20, he moved to New York, where he became involved in Harlem's numbers racket with gangster Dutch Schutlz throughout the 1930s. But as a Negro League team owner, executive, and talent scout, Pompez, also was one of a few pioneering Latino entrepreneurs who "widened the world of black baseball by introducing to the Negro Leagues the best Latino talent and creating opportunities for African Americans to play in Latin America." That was how Adrian Burgos Jr., in his book Playing America's Game: Baseball, Latinos, and the Color Line, describes Pompez's impact on baseball. Burgos rightly calls Pompez "one of black baseball's most significant executives." El Señor Was Only The First Although Pompez was enshrined in the Hall of Fame, Tampa's Al Lopez received that distinction back in 1977, the first Tampa native so honored. "El Señor," as he was nicknamed, also was the first Tampa native to reach the major leagues, debuting with Brooklyn on September 27, 1928. In 19 seasons as a catcher with Brooklyn, Boston, Pittsburgh, and Cleveland, Lopez caught a then-major league record 1,918 games and was a two-time All-Star. He also managed for parts of 17 more seasons, leading the 1954 Cleveland Indians to 111 victories before losing to the New York Giants in the World Series. Lopez, who died in Tampa on October 30, 2005, at age 97, also led the 1959 Chicago White Sox to the World Series. As a boy, Lopez would watch the Washington Senators, who held spring training in Tampa, and the local minor league Tampa Smokers, "hoping that I would improve by watching them." In his book, Florida's First Big League Baseball Players: A Narrative History, Lopez's biographer Wes Singletary writes how Lopez was discovered while playing in a Sunday amateur league in Tampa. Montoto, a sportswriter who worked for La Traduccíon, a Spanish newspaper in Ybor City, covered the game. He was so impressed with Lopez that he asked the teenager to practice with the Smokers. Montoto sent Lopez with a note to the Horseshoe pool hall to meet with Doc Nance, who was trying to rebuild the Smokers in 1925. After reading the message, Nance asked Lopez if a salary of $150 monthly would be okay. "I couldn't believe it," Lopez told Singletary. "I would have played for nothing." And thus began Lopez's journey to the majors. For decades, he remained Tampa's most prominent baseball product. Eventually, Tampa started producing more all-star caliber major leaguers. The 1960s through the 1990s saw Hillsborough County produce a flood of top major-league talent: Steve Garvey (Chamberlain High), Wade Boggs (Plant High School), Kenny Rogers (Plant City High School), Derek Bell (King High School), Lou Piniella and Dave Magadan (Jesuit); Dwight Gooden and Gary Sheffield (Hillsborough High School); Fred McGriff, Tino Martinez and Luis Gonzalez (Jefferson High School). In 1990, Piniella, then managing the Cincinnati Reds, and Oakland Athletics manager Tony La Russa–former Tampa American Legion Post 248 teammates–exchanged lineup cards at home plate for the start of the World Series. Martinez and Gonzalez, former Jefferson High teammates, went from the youth baseball fields of West Tampa to playing against each other in the 2001 World Series: Martinez for the New York Yankees and Gonzalez for the Series champion Arizona Diamondbacks. Gonzalez's soft liner won the series in the bottom of the ninth inning of Game 7. And in 2005, Boggs, who compiled 3,010 career hits and five American League batting titles, joined Lopez in the Hall of Fame. "Can you imagine if we had a reunion? All the guys from Tampa in one room?" Gonzalez told The Tampa Tribune in 2005. "Man, there would be some stories." Down On The Farm One of the more intriguing stories such a gathering might produce would be that of Charlie Cuellar's no-hit, no-run game against the Havana Cubans on July 23, 1947. Born in Ybor City in 1917, Cuellar was the "Marco Polo of the minor leagues," pitching for 15 different teams while compiling 253 victories with 130 losses from 1935-1950. In 1947, Cuellar pitched with his hometown Tampa Smokers of the Class C Florida International League. But Cuellar had surrendered seven runs in a game on June 18 against West Palm Beach. It was his fifth loss in what then-Times Sports Editor Wilber Kinley described as a "string of sorry performances by him." Cuellar's future with the Smokers was dangerous. "If he didn't pitch and pitch well, his employers had warned, he might as well prepare for a change of livery," Kinley wrote. Cuellar responded with his no-hitter as the Smokers won 5-0. The right-hander faced only 28 batters (one over the minimum) and allowed just three Cuban batters to reach first base, two on a pair of errors by Smokers third baseman Wiley Nash. "The most exciting game I can remember," Cuellar told Wes Singletary. "Many of the guys on my team were local Cubans, like me, so you can imagine it was a big deal playing against Havana." Local interest in those matchups was such that Plant Field had to be roped off to keep the overflow crowds of up to 8,000 from coming onto the field of play. "The tension in the game was so great," Cuellar said. "Any time Havana came to Tampa, the town would be in an uproar because so many Cuban people here rooted for Havana. The place went wild. There were seat cushions all over the field. The people were going bananas. It was such a big rivalry." Cuellar, "mixing his slider with a fast one that didn't let up on a single pitch," struck out eight batters. He retired the first 11 he faced and retired 14 in a row to end the game. But in the accounts of the day, it was the final out that proved to be controversial. Luis Suarez, a former Smokers player and friend of Cuellar's, "missed the third strike by a full two feet." Suarez "might or might not have tried to hit Cuellar's final pitch," Kinley wrote. "Some in the stands thought that Luis probably missed his swing purposely. Your guess is as good as the next about Suarez's intent." Cuellar's teammate, Bitsy Mott, had no doubts that Suarez struck out intentionally. Suarez "just waved at the pitches for the final out," Mott told Singleton. "I'm sure that did it for Charlie. It wasn't planned out in advance or anything like that, but the guy intentionally made the out." The Smokers went on to win 104 of 152 games that season and still finished second to the Cubans by two games. "Can you imagine?" Tony Cuccinello, who managed the Smokers, told the Tampa Tribune in 1994. "And [the Smokers] still finished two games back of the Cubans." Minor Developments Cuellar's Smokers were just one of several minor league teams to play in Tampa and St. Petersburg since minor league baseball first came to the area in 1919. That year, Tampa became a Class D Florida State League charter member. After finishing last in its first season, Tampa returned in 1920 with an 89-28 record, a .745 winning percentage still the best in league history. That season also was the year the St. Petersburg Saints joined the FSL. By 1922, the Saints won their first league title. The Saints eventually became the St. Petersburg Cardinals from 1966-96 while playing at Al Lang Field. Across the bay in Tampa, the Tarpons played at Al Lopez Park from 1957-88. Affiliated with the Cincinnati Reds for many years, the Tarpons sent players such as Pete Rose and Johnny Bench to the majors. Rose, baseball's all-time leader with 4,256 hits, led the Tarpons to their last FSL pennant in 1961, batting .331 with a league-record 30 triples in his only year in Tampa. "It was just Class A ball, and they used to draw many more mosquitoes than fans on most nights," Tampa Tribune columnist Joe Henderson wrote in 2004. "Pete made quite an impression, though." Boys Of Spring Before the minor leagues came to the area, major league teams used Tampa and St. Petersburg for spring training. The Red Sox's 1919 visit was just one of the early sojourns south for major league clubs, as Tampa Bay became a primary location for spring training for decades. Since 1913, 18 major league teams have called cities such as Tampa, St. Petersburg, Clearwater, Dunedin, Plant City, and Tarpon Springs their spring training homes. The first was the Chicago Cubs, lured by Tampa Mayor D.B. McKay's promise to cover the team's expenses, up to $100 per player. Nine days after arriving at Tampa's Union Station aboard Seaboard train No. 99 on February 17, 1913, the Cubs defeated the Cuban Athletics, a barnstorming Cuban amateur team, 4-2, as 6,000 fans packed Plant Field. According to Ray Arsenault's 1998 article, Spring Training in Florida–Our Roots Run Deep, vacationing William Jennings Bryan, soon to be sworn in as President Woodrow Wilson's secretary of state, was in attendance. Cigar workers and their families made up half the crowd as several Ybor City and West Tampa factories closed early to let employees attend. The following year, the St. Louis Browns became the first team to hold spring training in St. Petersburg, thanks to the efforts of Al Lang. A former laundry owner in Pittsburgh, Lang moved in 1910 to St. Petersburg, where he worked as the business manager of a ballpark. Wanting to improve a sagging local tourism industry, Lang sought to attract a major league team to train in St. Petersburg. He tried unsuccessfully to lure the Cubs and Pirates. "You must think I'm a damned fool, suggesting I train in a little one-tank town that's not even a dot on the map," Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss wrote Lang. On February 27, 1914, the Browns lost to the Cubs, 3-2, in St. Petersburg's first spring game. With fans riding trains from Tarpon Springs and boats from Tampa, an estimated crowd of 4,000 watched the game at a field near Coffee Pot Bayou. "Sunshine Al," for whom Al Lang Field was named, went on to lure the Boston Braves in 1922 and the New York Yankees in 1925 to the town that would twice elect him mayor. "Al Lang certainly had the betterment of baseball and St. Petersburg on his mind daytime and nighttime," Yankees manager Casey Stengel told the Petersburg Evening Independent after Lang died in 1960. "He knew baseball was a great advertisement for the city and state and carried that through to the fullest." Team Of Their Own But it would be many decades, and several failed attempts before Tampa Bay finally landed a major league team of its own. And the close calls were both exciting and heart-breaking. In 1988, the city of St. Petersburg had a deal in place to bring the Chicago White Sox to what was then called the Florida Suncoast Dome, but the deal fell through when Illinois Governor James Thompson lobbied the Illinois state legislature to put together an 11th-hour package to keep the White Sox in the Windy City. When Florida was awarded its first major league team, the Florida Marlins, for the 1993 season, fans in South Florida rather than Tampa Bay celebrated. In June of 1992, Major League Baseball owners approved the sale of the Seattle Mariners to an ownership group primarily backed by Japanese interests, ending any hope of moving the Mariners to St. Petersburg. But in August of that same year, hope again was rekindled when San Francisco Giants owner Bob Lurie agreed to sell his National League team to an ownership group headed by Tampa-area businessman Vince Naimoli. Those hopes, however, were crushed when National League owners, by a 9-4 vote, rejected Tampa Bay's application to buy the Giants. Finally, on March 9, 1995, baseball owners officially welcomed the Tampa Bay Devil Rays and the Arizona Diamondbacks as the 13th and 14th expansion teams in Major League Baseball history. On March 31, 1998, Tampa Bay's first official major league game was played at renamed Tropicana Field. The Rays lost 11-6 to the Tigers, a sign of things to come for a franchise plagued by front-office mismanagement, 100-loss seasons, and last-place finishes during its 10-year in existence. But the team now is under new ownership–headed by successful Wall Street investor Stuart Sternberg, who became the principal owner on October 6, 2005–that appears to have the once-foundering franchise turning in the right direction. And there are plans to convert Al Lang Field into a modern state-of-the-art stadium on St. Petersburg's waterfront. If all goes as hoped, the $430 million, retractable-roof, 34,000-seat, open-air ballpark could open as early as 2012. "Our vision is to build a breathtaking and contemporary waterfront ballpark," Sternberg said. "It will be an iconic landmark for the entire Tampa Bay region and showcase all that is great about Major League Baseball in Florida." CIGAR CITY MAGAZINE- MARCH/APRIL 2008 Art & Photography Contributors: Hillsborough County Public Library, Tampa Bay History Center, The Florida State Archives, The Tampa Tribune/Tampa Bay Times, University of South Florida Department of Special Collections, Ybor City Museum Society, private collections and/or writer. CESAR BRIOSOCesar Brioso was born in Havana, Cuba in 1965, Cesar Brioso graduated with a bachelor’s degree in journalism from the University of Florida in 1988. He has been a writer and editor at several newspapers in Florida such as the Miami Herald, (South Florida) Sun-Sentinel and Tampa Tribune. He was baseball editor at USA Today from 2003-2004 and curranty is the NOW Producer for USA TODAY Sports. FOLLOW CIGAR CITY MAGAZINE

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2013

Categories

All

|

Cigar City is a Florida trademark and cannot be used without the written permission of its owner. Please contact info@cigarcitymagazine.com

© 2021 Cigar City Magazine. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

© 2021 Cigar City Magazine. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed